Not all small cell lung cancers are the same.

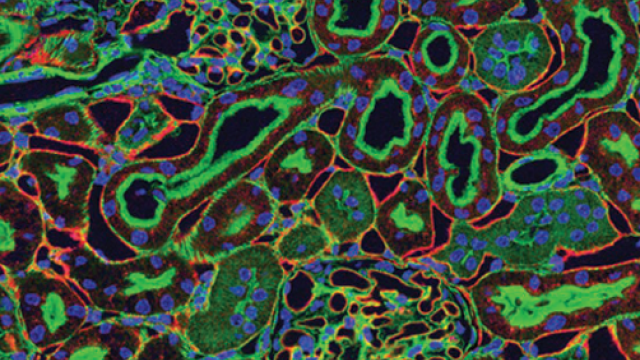

Identifying genetic features that make people vulnerable to small cell lung cancer can help physicians better treat patients with the disease. This image represents the genetic variations only recently found in different patients with small cell lung cancer. These newly found variations may help physicians select different treatment approaches that will work better for people with specific mutations. Credit: Pamela Beltowski, SPGM, FNL, NCI, NIH

About 30,000 people in the United States are diagnosed every year with small cell lung cancer (SCLC), the deadliest form of lung cancer. Patients are typically treated with a 30-year-old chemotherapy regimen and immunotherapy, which can work well initially. However, the cancer often comes roaring back, and most patients die within a year of their diagnosis. Progress toward improving that outcome has been notoriously elusive.

Lasker Clinical Research Scholar Anish Thomas, M.B.B.S., M.D., has long believed that patients with SCLC could benefit from a more precise approach. His vision is to find subgroups of SCLCs with genetic features that make them vulnerable to particular treatments, a strategy that has yielded success in other cancers. His team has now found some of the first molecular indicators that could be used to tailor SCLC treatments for patients.

Because lung cancer is so strongly linked to smoking, genetic risk factors and vulnerabilities for the disease have received little attention. Moreover, SCLC is typically diagnosed at an advanced stage where surgery is no longer a treatment option. For that reason, significant tissue samples that can be crucial to studying the genetic makeup of the disease are rarely obtained.

In work reported in Science Translational Medicine, Thomas’ team identified several inherited mutations that appear to increase an individual’s risk of developing SCLC. About ten percent of patients with small cell cancers were found to harbor inherited mutations in cancer-predisposing genes. Thomas and former postdoctoral fellow Camille Tlemsani, M.D., Ph.D., found that small cell cancer patients with these mutations, including patients with SCLC, responded better to standard chemotherapy and experienced a longer period of remission after treatment than patients without these mutations. Their work demonstrates that SCLC may also have an inherited predisposition and lays the groundwork for targeted therapies based on the genes involved.

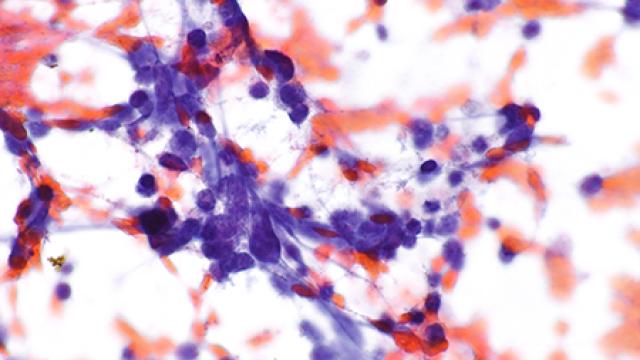

Another option for some patients with SCLC may be treatment with a combination of two U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs, topotecan and berzosertib. In an early clinical trial reported in Cancer Cell, Thomas and colleagues found that a combination of topotecan and berzosertib, used together in an experimental compound that interferes with a cell’s ability to repair damaged DNA, reduced tumors in about a third of patients with chemotherapy-resistant small cell cancers. Tumors that responded best shared a pattern of gene activity associated with extremely rapid growth and a high demand for DNA repair. This work, done in collaboration with Nobuyuki Takahashi, M.D., Ph.D., former NIH Hematology Oncology fellow, and Craig J. Thomas, Ph.D., Leader of Chemistry Technologies at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at NIH, provides the first evidence that targeting replication stress offers clinical benefit in cancer patients, and the combination regimen is now being investigated in two larger trials.

Finally, research published in Nature Communications points to a group of patients with SCLC who may be good candidates for immunotherapy. Beyond chemotherapy, immunotherapy benefits only a small percentage of patients with SCLC. Thomas and Physician-Scientist Early Investigator Nitin Roper, M.D., M.Sc., found that SCLC tumors, in which a developmental pathway called Notch was overactive, are more likely to respond favorably to immunotherapy that uses immune checkpoint inhibiting drugs.

SCLC remains one of the most challenging cancers to treat. By identifying subgroups and defining their specific vulnerabilities, Thomas and his colleagues aim to transform the way it is treated — moving from a one-size-fits-all approach to one that is more strategic, guided by the biology of each person’s disease.