Studying osteosarcoma in dogs may improve treatment options for people and pets.

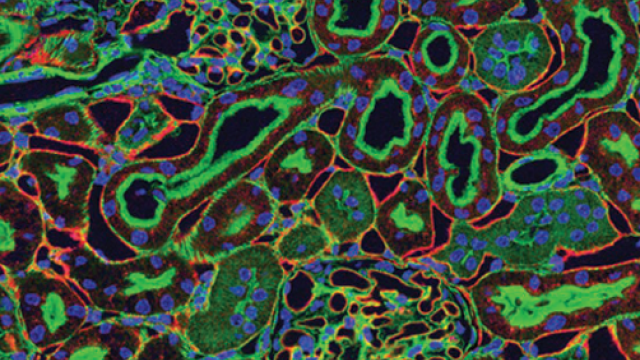

We may not be able to teach old dogs new tricks, but studying cancer in pet dogs can teach us new ways to treat both dogs and humans. Osteosarcoma is rare in humans, which makes it difficult to study. Unfortunately, however, it is common in dogs. CCR researchers have long studied naturally occurring osteosarcoma in pets. They recently found that molecular signatures for immune activity in dogs that had favorable clinical outcomes matched the signatures and outcomes in human patients. This research paves the way for improving treatment options for both four-legged and two-legged patients. Credit: iStock

Studying osteosarcoma, an aggressive bone cancer that most commonly occurs in teenagers and young adults, is very difficult because it is diagnosed in fewer than 1,000 people in the United States each year. For that reason, scientists in CCR’s Comparative Oncology Program (COP) are taking advantage of remarkable similarities between osteosarcoma in humans and dogs to improve treatment options for both people and pets.

In dogs, osteosarcoma is far more prevalent than it is in humans: U.S. veterinarians diagnose more than 10,000 cases of canine osteosarcoma annually. Senior Scientist and COP Director Amy LeBlanc, D.V.M., says studying osteosarcomas in pets helps researchers learn how the disease behaves when it arises naturally, complementing studies in laboratory models. “Studying dogs with cancer provides another piece of a really complex puzzle and helps give us insight into how cancers form and respond to therapy,” she says.

Twenty academic veterinary centers in the United States and Canada participate in the NCI’s Comparative Oncology Trials Consortium, which runs clinical trials to assess novel cancer therapies in pet dogs. As they investigate experimental osteosarcoma treatments in their canine patients, their insights are informing the design of human clinical trials. One recent study, reported by LeBlanc and her team in Communications Biology, offers the most detailed description yet of clinical and molecular similarities between the human and dog form of the disease — and points toward potential treatment strategies for both.

LeBlanc and her colleagues examined how osteosarcoma’s molecular makeup influences its behavior by analyzing tumor samples from nearly 200 dogs. Some of the dogs had better clinical outcomes than others, surviving longer after their osteosarcoma diagnosis or remaining disease-free longer following treatment. LeBlanc’s team, led by postdoctoral fellow Joshua Mannheimer, Ph.D., found that these outcomes were related to patterns of activity of particular genes in the tumors. Remarkably, the same molecular signatures also correlated with clinical prognosis in human patients with osteosarcoma.

LeBlanc says the composition of those prognostic gene signatures provides clues about the biological factors that influence osteosarcoma outcomes. Many of the genes that comprise the signatures help shape tumor cells’ interactions with the immune system, suggesting more anti-tumor activity occurred in the osteosarcoma patients that fared better. “That speaks to one of the big pictures that we're learning about cancer,” LeBlanc says. “The more that your immune system is aware and active, the better the outcome you may have as a patient, whether you're four-legged or two-legged.”

A next step will be to investigate why many patients, both human and canine, lack a strong immune response to osteosarcoma and how their immune systems could be empowered to control their cancer. Laboratory studies of immune cells’ interactions with osteosarcoma tumors will complement NCI-supported clinical trials investigating immunotherapy treatments for canine osteosarcoma and could set the stage for more targeted therapies in dogs and humans. “There's a huge amount of value in studying dogs and the diseases they get, and we’re just getting started,” LeBlanc says.