An immune signal that reprograms fat metabolism could help control nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

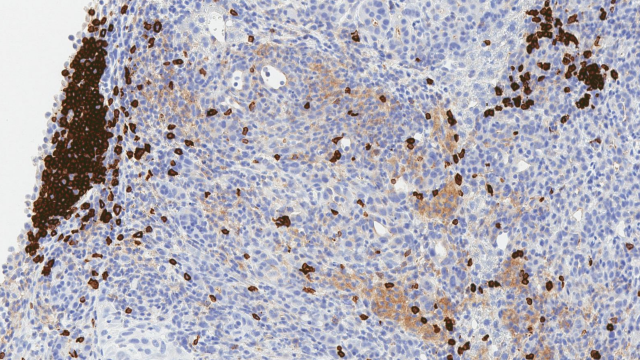

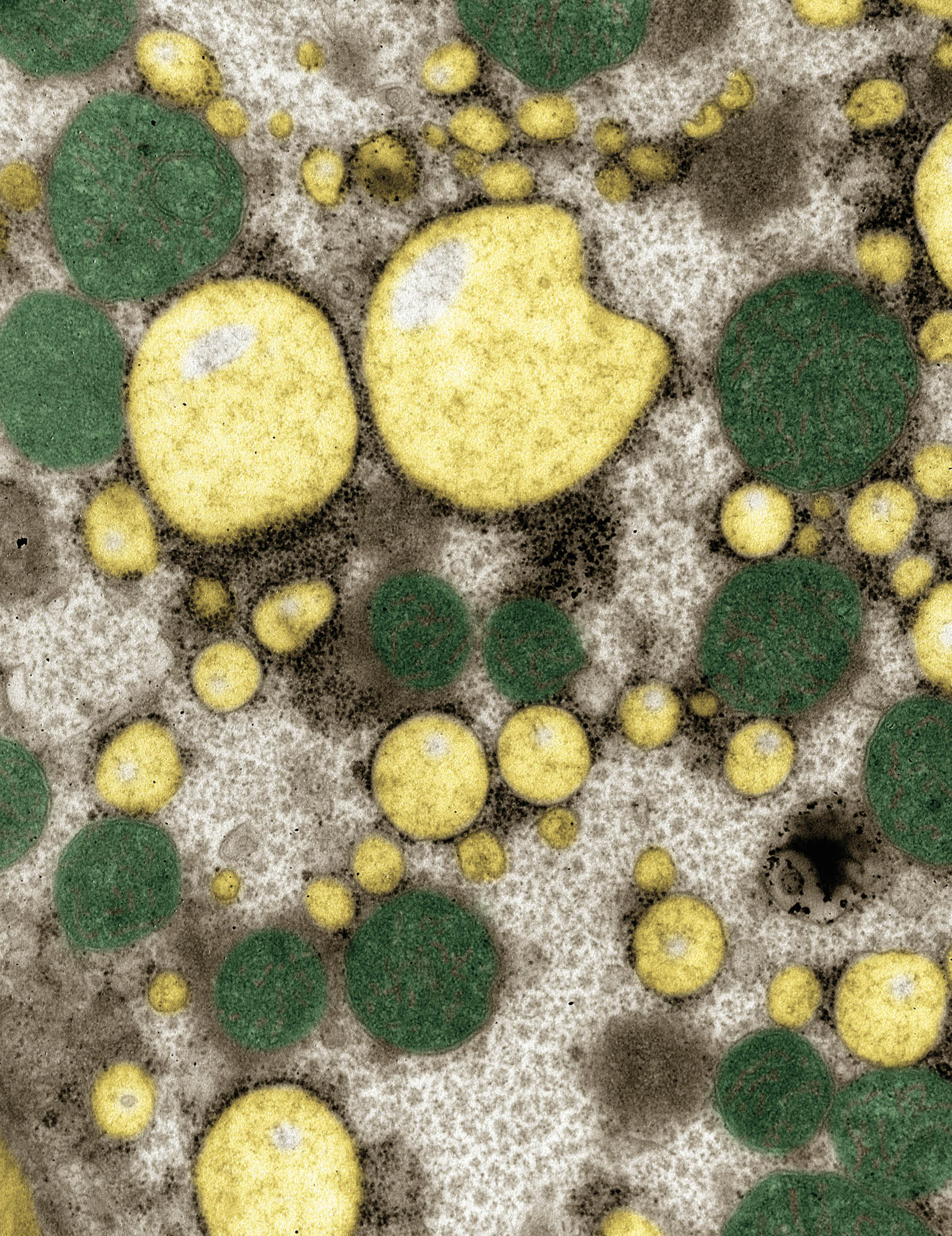

This colored transmission electron micrograph shows a cross section of liver tissue with a case of fatty liver disease. If left untreated, fatty liver disease can result in scar tissue, reduced liver function and sometimes liver cancer. This study has now identified a molecule released by macrophages (a type of immune cell) that helps the liver cope with excess fat, and which could be harnessed to help control nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Credit: IKELOS GmbH, Dr. Christopher B. Jackson, Science Source

Nearly one in three people worldwide are thought to have an excess accumulation of fat in their liver. The condition, known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, usually exhibits no symptoms of its own but it puts people at risk for diabetes and other metabolic disorders. When it becomes severe, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease can damage the liver and may lead to liver cancer.

The liver handles most of the breakdown of fats in the body. When high levels of fats are taken in through the diet, the liver can become overwhelmed, so patients with excess fat in their liver are usually advised to control their weight with diet and exercise. A discovery from the lab of Senior Investigator Daniel McVicar, Ph.D., suggests it may also be possible to reduce fat deposits in the liver by directing liver cells to process fats more efficiently.

When high levels of fat are present in the liver, immune cells called macrophages are summoned to the organ, where they respond to the threat by releasing a molecule called itaconate. McVicar and his team reported in Nature Metabolism that itaconate helps the liver deal with the excess fat.

Staff Scientist Erika Palmieri, Ph.D., and Associate Scientist Jonathan Weiss, Ph.D., studied this process in mice. When laboratory mice are fed a diet that is high in fat, mimicking a typical Western diet, fat builds up in the animals’ livers. When McVicar’s team genetically manipulated mice so they could not make itaconate, their livers accumulated even more fat and the mice became obese. These mice also developed metabolic problems that did not arise in itaconate-producing mice that were fed the same food.

The researchers suspect itaconate helps mitigate fat accumulation in human livers, too. They found elevated levels of the compound in samples of liver tissue from patients with a severe form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). In NASH, excess fat causes the liver to swell and become damaged. The researchers say the high levels of itaconate in the damaged livers could be a sign the immune system is trying to help the liver cope with the excess fat. “In disease, this loop gets overwhelmed and can't control the condition anymore,” McVicar says. “But it’s trying.” Without itaconate, he says, patients’ livers might have retained even more fat and accrued even more damage.

McVicar’s team found that mice without their own itaconate became more resilient to the effects of a high-fat diet when they were administered an itaconate-like compound. The findings suggest similar compounds might help rein in fat accumulation in people whose diet promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Controlling that condition could reduce metabolic complications like diabetes and ultimately lower the risk of liver cancer.