Studies identify a marker of treatment response for patients with advanced, drug-resistant ovarian cancer.

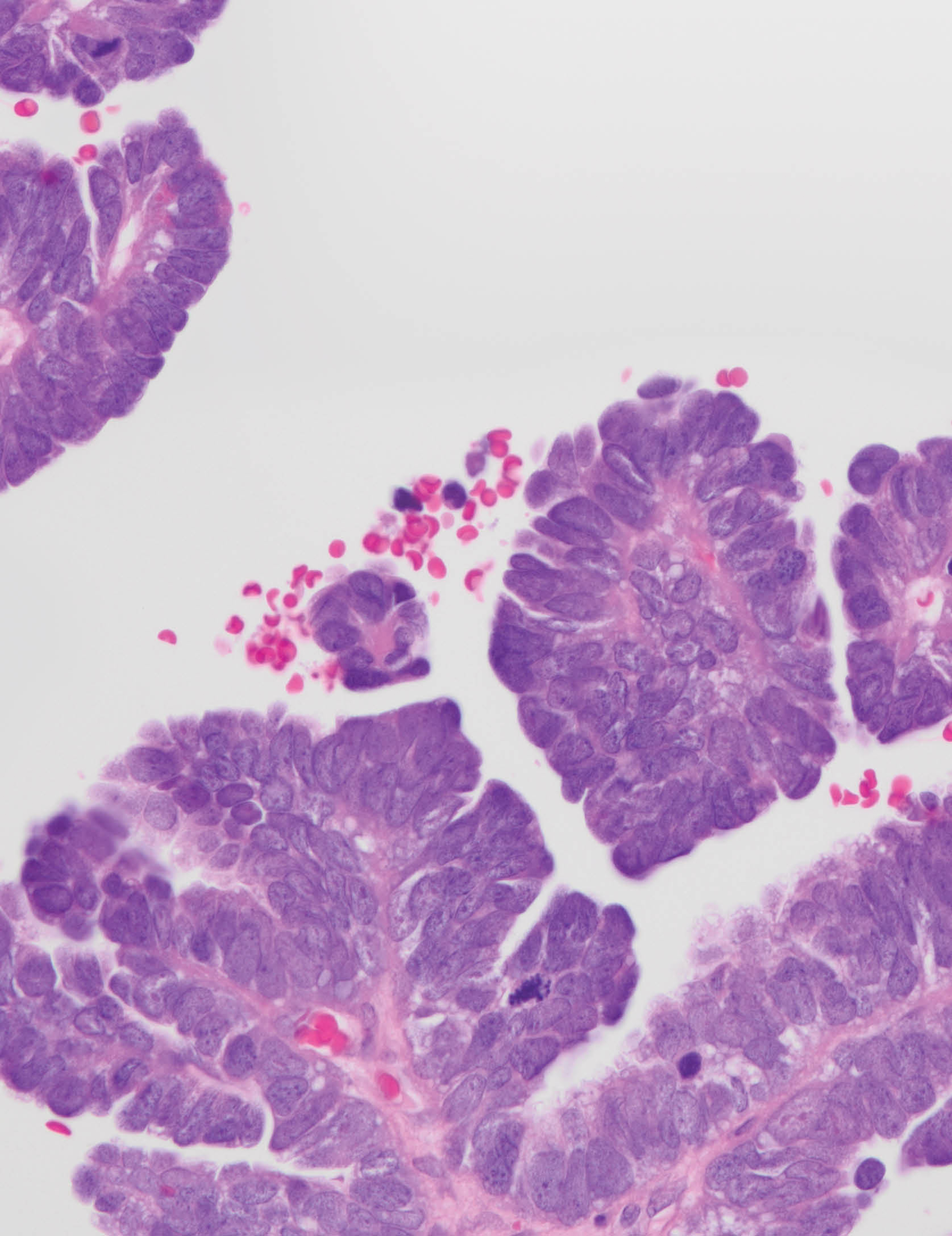

High-grade serous carcinoma ovarian cancer cells with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Ovarian cancer is often diagnosed when it is already advanced, and treatment options are often limited. CCR researchers have now identified a drug that could be beneficial for a subset of patients whose cancer has grown after treatment with PARP inhibitors. They have also identified the gene activity that may indicate which patients are good candidates for the new drug. A clinical trial to evaluate its effects is underway. Credit: Maria Del Carmen Rodriguez Pena, M.D., CCR, NCI, NIH; Markku M. Miettinen, M.D., Ph.D., CCR, NCI, NIH; SPGM, FNL, NCI, NIH

Ovarian cancer often goes undetected until it has become advanced, and it is the most lethal of all gynecological cancers. Nearly a decade ago, the outlook for people diagnosed with ovarian cancer improved when drugs called PARP inhibitors were approved as a treatment for the disease. However, a new challenge has emerged for doctors who treat ovarian cancer: how to treat patients whose cancer has become resistant to PARP inhibitors, as most eventually do.

One doctor working to address this challenge is Lasker Scholar Tenure-Track Investigator Jung-Min Lee, M.D. Through laboratory and clinical studies, Lee has identified a class of drugs that may stop tumor growth for a subset of patients whose ovarian cancer no longer responds to PARP inhibitors. She and her team, including Medical Research Scholars fellow Nitasha Gupta, M.D., research fellow Tzu-Ting Huang, Ph.D., and biologist Jayakumar Nair, Ph.D., reported their findings in Science Translational Medicine.

PARP inhibitors interfere with cells’ ability to repair damaged DNA. They are particularly effective at eliminating cancer cells whose DNA repair systems are already impaired due to mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. Today, many patients with ovarian cancer use PARP inhibitors as maintenance therapy after their initial treatment, and the drugs can keep cancer at bay for years. Eventually, however, most cancer cells develop resistance to the drugs.

Lee worked with the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at NIH to determine how thousands of different chemicals affected the growth of ovarian cancer cells that, like many of her patients’ cancers, are resistant to PARP inhibitors and have mutations in BRCA genes. One of the best killers of those cells was the experimental cancer therapy prexasertib, which inhibits an enzyme called CHK1.

Lee and her colleagues then tested prexasertib in a clinical trial involving 17 patients with PARP inhibitor-resistant ovarian cancer. Four patients saw their tumors shrink or stabilize for at least six months following the treatment. While not everyone in the trial benefitted from the drug, Lee reasoned that it might be possible to identify the best candidates for prexasertib treatment based on their tumors’ molecular makeup.

Armed with data and tumor samples collected during the clinical trial, she went back to the lab. “Even if we don't see a dramatic response in the majority of people, when we have a biologically relevant hypothesis, we can learn from that,” she says.

She and her team discovered that the cancer cells from patients who benefited from the treatment had unusually high activity in two genes: Bloom syndrome RecQ helicase (BLM) and cyclin E1 (CCNE1). They confirmed that PARP inhibitor-resistant BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer cells are more sensitive to CHK1 inhibitors when both BLM and CCNE1 are overactive.

These findings have informed the design of a clinical trial that Lee is leading to evaluate prexasertib’s effects in patients with ovarian, endometrial or bladder cancer. Because of the treatment’s potential to address an urgent need for patients with advanced ovarian cancer, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has granted a fast-track designation to speed prexasertib’s evaluation.

“My ultimate goal is to improve the clinical outcome of my ovarian cancer patients,” Lee says. “I feel like I have to figure out something for this critically important and emerging patient population I see in the clinic.”