A second look reveals a highly effective lymphoma treatment.

A second look at data from the PHOENIX trial yielded amazing results and appropriately generated new life for the aptly named study. Most patients enrolled in the large, international trial to test the combination of a new targeted drug, ibrutinib, and chemotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) did not benefit enough from the treatment, but a well-defined subset of patients did. Here, the mythical phoenix bird rises from the ashes to new life. Credit: Erina He, NIH Medical Arts

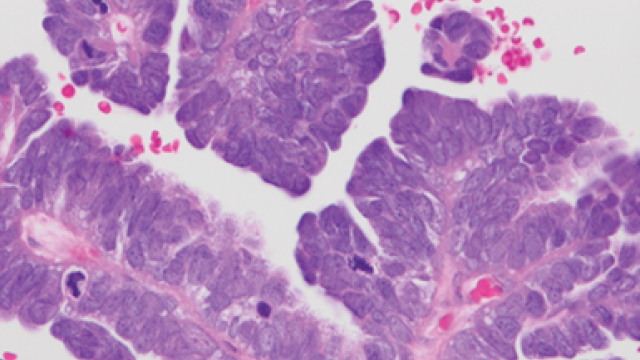

Senior Investigators Louis Staudt, M.D., Ph.D., and Wyndham Wilson, M.D., Ph.D., have been working together at CCR for decades to develop targeted therapies for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). While Staudt conducts the basic science experiments, Wilson leads the clinical work. Their expectations were high when one of those therapies was tested in a large, international trial called PHOENIX. On paper, it should have been an effective anti-cancer treatment, yet when all data was analyzed, the trial fell short of its expectations and was deemed unsuccessful.

However, digging just a little deeper, Staudt and Wilson conducted an analysis of a subset of the PHOENIX data. They report in a study published in Cancer Cell that the drug being investigated, a cell signaling inhibitor called ibrutinib, in combination with standard chemotherapy, was highly effective in patients under the age of 60 with some subtypes of lymphoma — resulting in 100% event-free survival and 100% overall survival after three years.

“The results were the most amazingly perfect example of precision medicine that you would ever want to see,” says Staudt. “We had preliminary reasons to think that people with certain subtypes of DLBCL should respond to ibrutinib, which were supported beautifully by the trial results.”

In earlier pioneering work, Staudt had identified genetically unique subtypes of DLBCL, including some subtypes that rely on B cell receptor (BCR) signaling to survive. Subsequently, ibrutinib was developed as an anti-cancer drug to block this mechanism. The first analysis of the PHOENIX study data, however, did not show a large enough improvement in outcomes for all patients for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to approve ibrutinib for this indication. “We thought not approving ibrutinib was basically throwing the baby out with the bath water, if you will,” says Wilson.

Louis M. Staudt, M.D., Ph.D.

Chief

Wyndham Wilson, M.D., Ph.D.

Senior Investigator

Lymphoid Malignancies Branch

Motivated by their extensive understanding of the molecular features of various DLBCL subtypes, Staudt and Wilson decided to revisit the data. In their re-analysis of the PHOENIX outcomes, every person under the age of 60 with DLBCL subtypes called MCD or N1 who was given ibrutinib in combination with chemotherapy was still alive after three years. Those with the MCD or N1 subtypes who received only chemotherapy had survival rates of 70% and 50%, respectively. For people over the age of 60, the combination of ibrutinib with chemotherapy was associated with too many severe side effects, which made the use of the drug impractical for them, hence the initially unsatisfactory results.

Staudt and Wilson note that their unique position at CCR — where they can conduct a follow-up study without needing to apply for a grant — was critical for confirming ibrutinib’s potential as a targeted therapy. Their partnership, as well, where basic science and clinical data are used in tandem to advance science, has been key to their success, they say.