Breast cancer cells undergo dangerous reprogramming within passageways that connect tumors to the bloodstream.

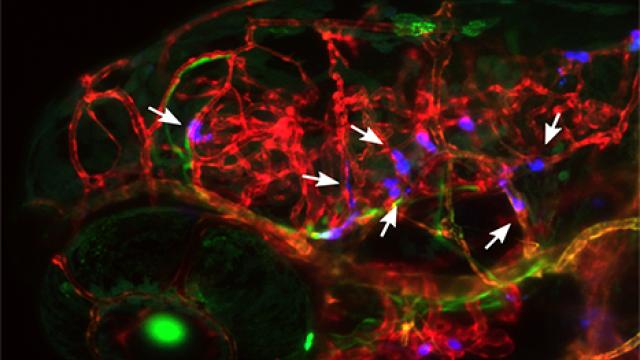

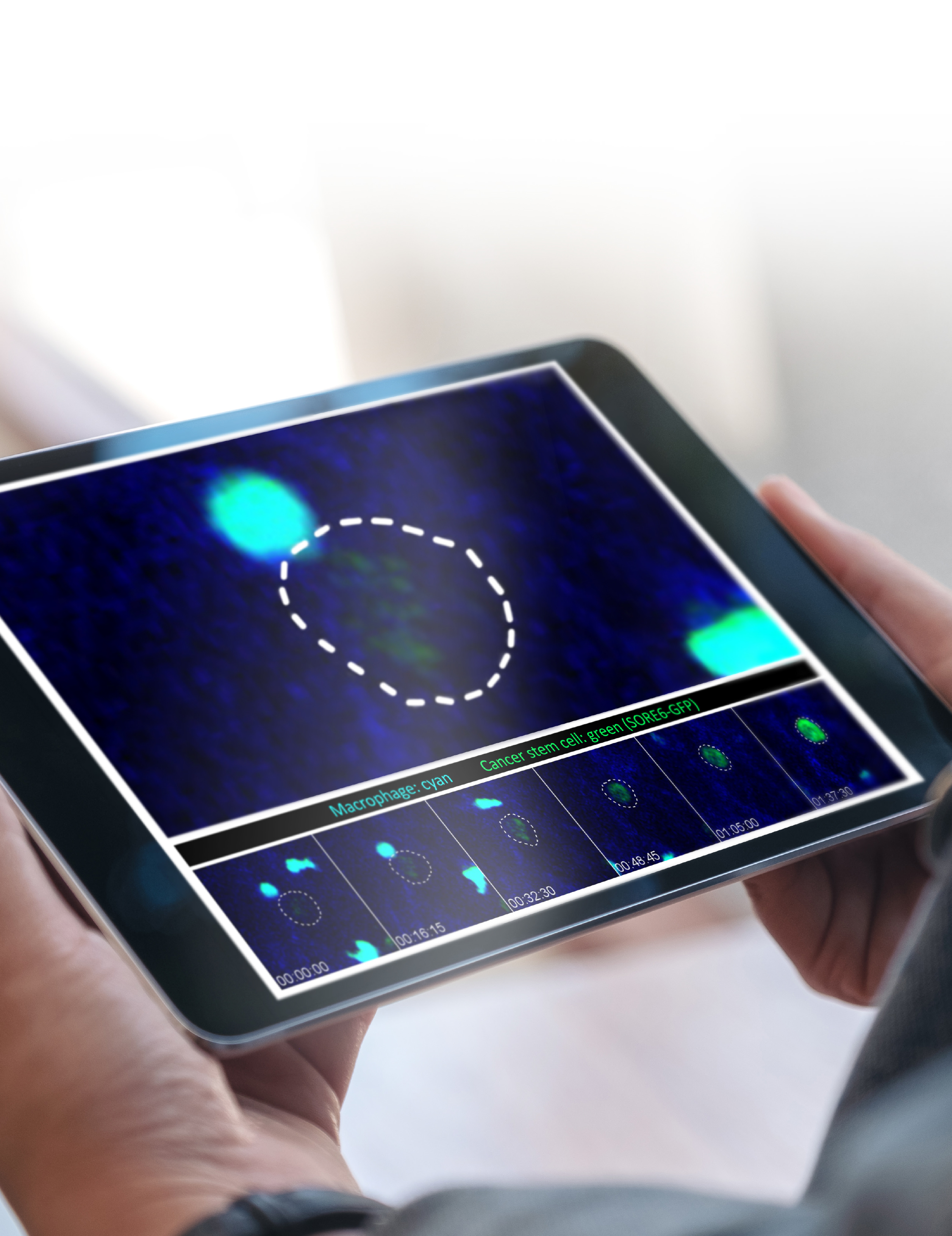

To access the bloodstream and travel to other parts of the body, cancer cells must pass through a portal made up of three cells. In transit, the cancer cell is “kissed” by one of these three — a macrophage — and the cancer cell takes on new stem cell-like properties. Using a biosensor that lit up when the cell took on these new attributes, CCR researchers and colleagues at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine were able to record this transformation. Stills from the video of the “macrophage kiss” can be seen here. A better understanding of this process may help researchers prevent cancer from spreading. Credit: Ved P. Sharma, Albert Einstein College of Medicine; iStock

Cancer’s excessive, uncontrolled growth is its most malicious trait. But there is reason to believe that only a tiny and elusive subset of cancer cells truly drive a tumor’s growth: the so-called cancer stem cells. These cells’ unusual resilience and ability to divide in stressful settings may also make them efficient instigators of metastasis, which occurs when cells break off from a primary tumor and make their way to other locations in a patient’s body, often via blood vessels.

Senior Investigator Lalage Wakefield, D.Phil., and her colleagues watched cancer cells as they began their metastatic journey in mice using a microscopy technique developed by collaborators Maja H. Oktay, M.D., and John Condeelis, Ph.D., at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York. Working with a biosensor developed in Wakefield’s lab, they found that many of those cells took on properties of cancer stem cells the moment they broke free of a tumor.

Because the biosensor lights up when cancer cells take on stem cell properties, Wakefield and her team could watch in real time as human breast cancer cells left tumors and entered the bloodstream in living mice. They were able to capture a movie of this transformation and their observations were reported in Nature Communications.

To access the bloodstream, breast cancer cells must pass through specific portals that connect the tumor surface to a blood vessel’s outer wall. Three different types of cells come together to form these portals, and it was one of these — the macrophages — that the researchers found triggered migrating cancer cells to take on the properties of cancer stem cells. Macrophages are a type of white blood cell, some of which can support tumor growth and metastasis.

“We observed a number of instances where, when a non-stem cancer cell came into close proximity with the macrophage, the macrophage turned it into a cancer stem cell. That interaction — a cellular ‘kiss’ — essentially gave your standard tumor cell the superpowers of a cancer stem cell,” Wakefield says. Following the transformation, she says, cancer cells would have heightened abilities to disseminate through the body, invade tissues and resist most types of cancer therapy.

Since every cancer cell that passes through a portal into a blood vessel must squeeze past a macrophage, these interactions happened over and over again. While only about 1% of the cells in the primary breast tumors they studied were cancer stem cells, Wakefield and her colleagues found that more than 60% of tumor cells had taken on that more aggressive identity by the time they entered the bloodstream.

Incidentally, in patients with breast cancer, high densities of tumor-to-blood-vessel portals are associated with an increased risk of metastasis. Wakefield’s team has identified the signal that macrophages use to trigger tumor cells’ transformation to cancer stem cells. The next step? They think it may be possible to block the dangerous reprogramming that goes on within these cellular passageways.