To fight cancer, T cells must first overcome a tumor’s hostile environment to reach their target.

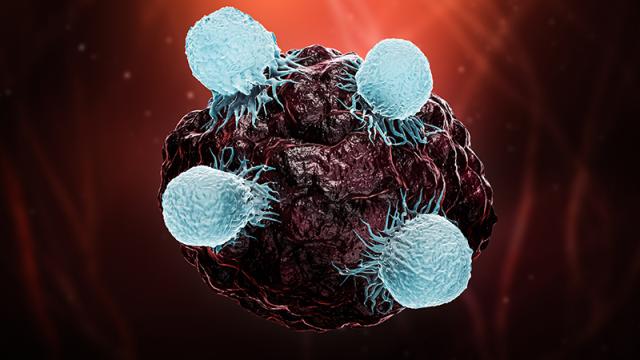

T cells, shown here as smaller blue cells attacking a larger cancer cell, are a crucial part of the immune system’s fight against cancer. But many cannot survive in the often-hostile environment that surrounds the cancer cells. A new tool will help identify the biomarkers of T cells that mark them as resilient to this harsh environment and allow them to persist in their pursuit to destroy cancer cells. Credit: iStock

Many cancer immunotherapies work by bolstering a patient’s T cells. However, in solid tumors, the tumor microenvironment that surrounds the cancer cells can be treacherous, and not all T cells are well equipped to survive it. If one could predict the resilience of a patient’s T cells in this hostile environment, more effective immune-directed treatments could be developed.

A team of CCR researchers, led by Stadtman Tenure-Track Investigator Peng Jiang, Ph.D., has created a computational tool called Tres (tumor-resilient T cell model) that analyzes gene activity in T cells to determine their resilience in a tumor environment. The tool will help researchers better evaluate an individual’s treatment options and find the best possible treatment. The team’s findings were published in Nature Medicine.

“One common approach in our work as a data science lab is to develop computational models that can repurpose large amounts of existing data to reveal new findings,” Jiang says. For example, cells have a lot of information in their transcriptomes, which are catalogs of expressed genes that characterize a cell’s unique profile and how it functions.

To build the Tres model, Trang Vu, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in Jiang’s lab, and Yu Zhang, M.D., Ph.D., a visiting graduate student, used existing patient single-cell RNA molecule transcriptomes to identify T cells that have gene signatures that allow them to proliferate even when exposed to a highly immunosuppressive tumor environment.

Applying this model to T cells from patients with melanoma, breast, lung or blood cancers, Vu and Zhang calculated resilience scores to predict how well the cells survived in the tumor environment. They found that patients with the most resilient T cells were more likely to respond well to immunotherapy and the resilience scores accurately predicted outcomes for patients that underwent various types of immunotherapies.

In addition to predicting patient response, Jiang found that Tres can also be used to discover new T-cell regulators that can be targeted to enhance T-cell function. As proof of principle, Jiang’s team linked the activity of a gene called FIBP to T-cell resilience and discovered that turning it off boosted the ability of T cells to kill cancer cells in cultured cells and in mice. “This finding highlights FIBP as a potentially important drug target,” Jiang says. “The gene may serve as a metabolic switch that can make the T cells more effective.”

Tres is freely available online for public use. “Our tool can be used by anyone in the cancer research community to uncover new biomarkers,” says Jiang. “We hope it will provide useful insights to improve current immunotherapies and develop new treatment options as well.”