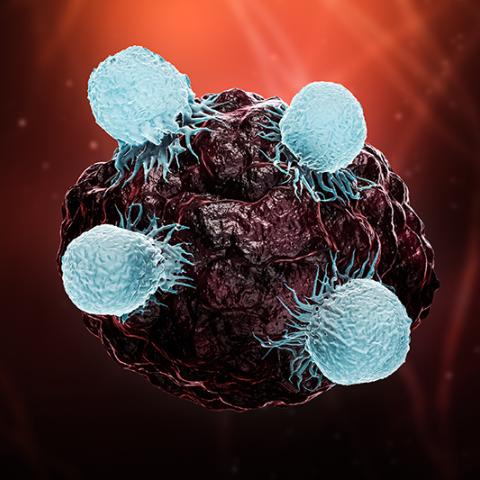

T cells can destroy cancer, but first they must overcome the tumor’s immunosuppressive signals. Shown here, a group of killer T cells (light blue) surround a cancer cell (dark red/black).

Image credit: iStock

A new computational tool from CCR scientists called Tres (tumor-resilient T cell model) analyzes gene activity in T cells to assess how those cells are likely to fare in an immunosuppressive environment. The tool’s developers reported on May 2, 2022, in Nature Medicine that this measure of T cell resilience can predict whether cancer immunotherapy will be an effective treatment for an individual patient.

Tumors are treacherous places for T cells, says Peng Jiang, Ph.D., a Stadtman Investigator in the Cancer Data Science Laboratory who led the research. The immunosuppressive signals produced by cancer cells are thought to be a key reason immune checkpoint inhibitors and adoptive cell therapy, which both aim to empower patients’ T cells to eliminate cancer, have had limited success in treating solid tumors. Even T cells that are well equipped to destroy cancer cells cannot succeed unless they overcome those signals.

“The T cells need to survive on a really bad battlefield,” Jiang says. “So it is really important that they are resilient.”

To find out what it takes for a T cell to persist inside a tumor, Trang Vu, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow and iCURE scholar in Jiang’s lab, and Yu Zhang, M.D., Ph.D., a former visiting graduate student, turned to data from patient tumor samples in which the gene expression of individual T cells had been measured. They used that information to infer the extent of the cells’ exposure to immunosuppressive signals. Then they used the same data to evaluate how actively the T cells were growing. Combining these analyses, Zhang and Vu were able to identify T cells that grew well even in the most immunosuppressive environments.

When they applied this analysis to T cells from patients with melanoma, lung, breast, or blood cancers, they found that patients with the most resilient T cells were the most likely to have responded well to immunotherapy. Resilience scores for T cells from tumor samples taken prior to treatment (and prior to the manufacture of cell therapies) predicted outcomes for immune checkpoint blockade and adoptive cell therapy, two of the most common types of immunotherapy. That suggests Tres can help patients and their doctors evaluate treatment options, Jiang says. Researchers and clinicians can use Tres online to calculate resilience scores for their own samples using bulk gene expression data.

Tres also offers researchers a way to identify genetic factors that support T cells’ survival in inhospitable environments. Jiang’s team used Tres to link the low activity of a gene called FIBP to T cell resilience. Collaborating with CCR investigators Glenn Merlino, Ph.D., Senior Investigator in the Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics, Chi-Ping Day, Ph.D., a scientist from the Merlino Lab, Kenneth Aldape, M.D., Chief of the Laboratory of Pathology, and Xin-yuan Guan, Ph.D., at the University of Hong Kong, they found that eliminating FIBP allows T cells to kill cancer cells more effectively in both mice and laboratory dishes. Their experiments suggest that the absence of the gene slows the metabolism of cholesterol, a known inhibitor of effector T cell function.

Learn more about the iCURE program here.

Learn more about fellowship opportunities within CCR here.