A 30-year trial leads to a highly effective treatment.

In 2009, Troy Kamphuis learned that he had tumors on his lungs, liver, spleen and colon, but months of testing yielded no diagnosis. Suspicious that Kamphuis might have an extremely rare disease called lymphomatoid granulomatosis, his medical team sent tissue samples to the only doctor in the U.S. specializing in the disease at the time, Wyndham Wilson, who confirmed their hunch. Eager to learn more, Kamphuis called the number on Wilson’s website. “Lo and behold, Dr. Wilson picked up the phone!” says Kamphuis. “That turned out to be my small miracle.” Kamphuis decided to skip his first chemotherapy treatment the following Monday and instead fly from Boulder, Colorado, to the NIH Clinical Center in Maryland where he joined Wilson’s clinical trial and received treatment with interferon. Within two months, Kamphuis’ scans showed no lesions or tumors. He continued taking interferon for one year before stopping altogether. “I wrapped up treatment in early 2011 and have been fine ever since,” says Kamphuis, emphasizing that his whole experience with NIH — including the faculty and staff — was excellent. Credit: Adam Kamphuis

Decades ago, nobody knew the cause of lymphomatoid granulomatosis, a rare and life-threatening disease that affects the immune system. But now, CCR researchers, in a clinical trial conducted over 30 years, have identified a treatment that cures the disease in a significant portion of patients and dramatically extends life expectancy by twenty years for others.

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is a precancerous condition in which the body produces many abnormal immune cells that accumulate in and damage healthy tissues. “When I started studying this disease back in 1990, there was no standard therapy for it and the median survival was somewhere around 6 months,” says Senior Investigator Wyndham Wilson, M.D., Ph.D.

At the time, emerging evidence suggested that the disease was triggered by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which infects immune cells. Most people are infected with EBV by adulthood and face few, if any, consequences, because their immune system successfully suppresses it for the rest of their life. However, in extremely rare cases, the immune system fails to control the virus, which triggers the growth of abnormal immune cells, leading to lymphomatoid granulomatosis and the development of lesions in critical organs.

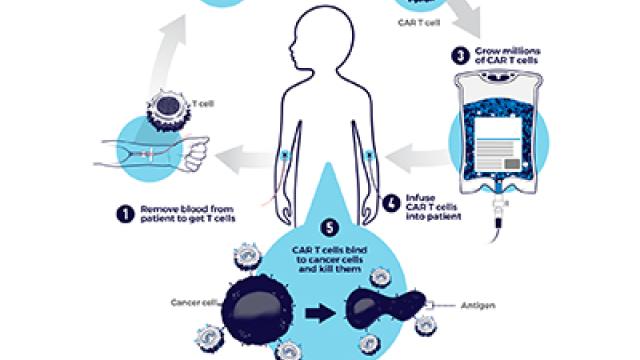

Shortly after Wilson joined NCI, some of his CCR colleagues were finding the first indications that lymphomatoid granulomatosis was due to defects in a type of immune cell called a B cell. Based on what was known about the disease, Wilson suspected that a relatively novel drug at the time — interferon, a form of immunotherapy — could help treat it. He tested this theory in a few patients, and “in three out of four patients, the disease went away,” says Wilson, noting the effect was sustained after therapy was discontinued less than two years later.

Given the rarity of lymphomatoid granulomatosis, recruiting enough patients for a large clinical study to prove the therapy’s efficacy was a major challenge. It took over 30 years to enroll 67 patients in his phase 2 trial.

“Nowhere else would you be able run a study for 30 years, bringing in two to three patients per year, and get the funding for it,” says Wilson, noting that the trial was possible thanks to NCI infrastructure, funding and experts.

In the trial, 45 patients in the early stages of their disease were given the immunotherapy interferon alfa-2b, while 18 patients with more advanced disease were treated more aggressively with chemotherapy.

The results, reported in The Lancet Haematology, turned out to be a game changer for patients. Among those initially treated with interferon alfa-2b, 61 percent had a complete response, which meant their lesions shrunk substantially and no new lesions formed for at least three months. Among those treated with chemotherapy, 47 percent had a complete response. What’s more, if a patient didn’t respond to their initial treatment with immunotherapy or chemotherapy, they were given the other treatment in a cross-over experiment, which resulted in even more responses.

“In a nutshell, using this strategy, we changed the average survival time from six months to over 20 years! And we really were able to, for the first time, eradicate this disease in most folks,” says Wilson, noting that two patients he treated in the initial study, who were in their 30s at the time, are still alive today. “It is very gratifying.”