Combining immunotherapies could make it harder for cancer cells to become treatment-resistant.

Terry Fry, M.D., a former Investigator in the Pediatric Oncology Branch, discusses treatment with Bo Cooper. Bo was featured in the “First in Human” documentary series from Discovery Channel as a patient on Dr. Fry’s clinical trial using the CD22 CAR T-cell therapy. Bo passed away in 2016 after a long battle with acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Credit: “First in Human,” Discovery Channel

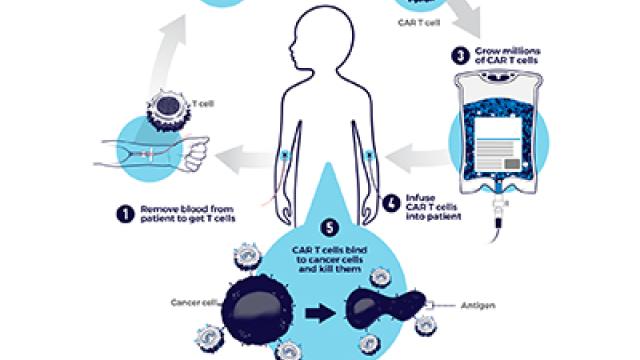

Strategies in which patients’ own immune cells are genetically modified to fight their cancer, called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies, have emerged recently as revolutionary new therapies. In 2017, two such treatments were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, including one that causes remissions in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Now, CCR scientists led by Terry Fry, M.D., an Investigator in the Pediatric Oncology Branch (POB) at the time the work was done, and Crystal Mackall, M.D., a former POB member, have had success in treating ALL with a new, related approach. Their results raise the possibility of combining multiple immunotherapies to improve patient outcomes.

The recently approved CAR-T immunotherapies arm the immune system to destroy cancer cells carrying a surface marker called CD19. The newer treatment is a CAR T cell that targets a different marker, CD22, found on many leukemia and lymphoma cells. After Fry and Mackall’s team tested the CD22 CAR therapy in mice, a phase I trial was launched at the NIH Clinical Center to test the therapy in patients. Fry and colleages have shown that targeting CD22 can lead to responses similar to those targeting CD19 in patients with ALL. That raises the intriguing possibility that a patient’s remissions may be prolonged by developing a CAR T-cell therapy that targets both CD19 and CD22.

Although CD19-targeted CAR-T therapies have generated complete remissions in children whose cancers relapsed or failed to respond to chemotherapy, many patients eventually relapse as their cancers develop resistance to the CAR-T treatments. Typically, this is because their cancer cells have lost the CD19 marker that flags them as targets to the engineered cancer-fighting T cells.

The research team, which also included Nirali Shah, M.D., an Associate Research Physician in the Pediatric Oncology Branch, reported in Nature Medicine that 12 of 22 patients achieved complete remissions after receiving the engineered T cells. Notably, the treatment was effective in patients who had relapsed after treatment with CD19-targeted therapies and in patients whose cancer cells lacked the CD19 marker.

Now that it is clear that CAR T cells can effectively target CD22-bearing leukemia cells, Fry and colleagues are optimistic that they can achieve even better results for patients by developing a combined approach targeting both CD19 and CD22. The first combinatorial trial to test CD19 and CD22 opened in February 2018.

Reference

Fry T, et al. Nature Medicine. 2017 Nov 20; (24):20–28.