An understudied immune cell can exhibit potent anti-tumor activity against liver cancer.

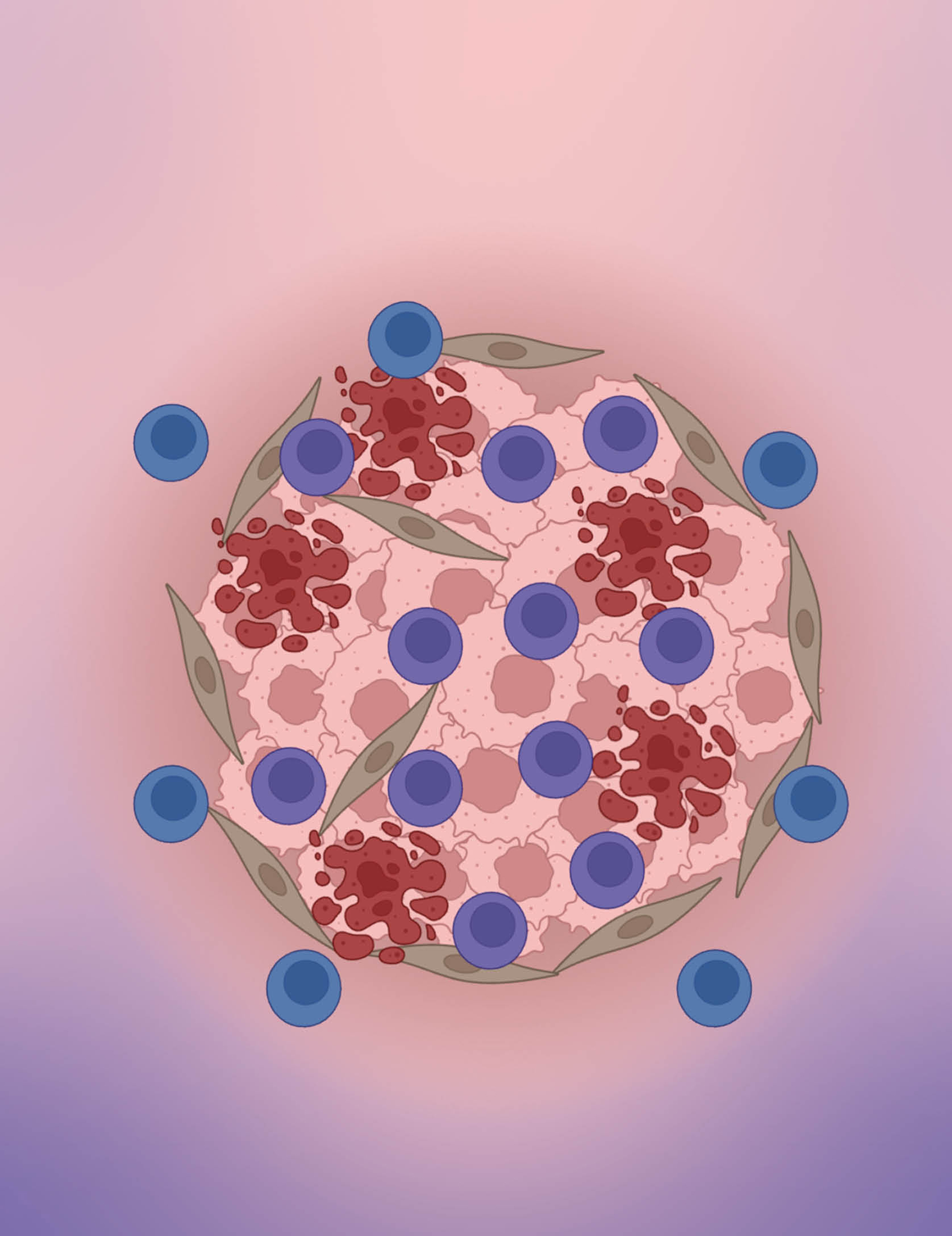

Despite their potential to attack cancer cells, MAIT cells (shown here in blue) often surround liver tumors but fail to infiltrate them. New findings suggest that this is due to an interaction with macrophages that also surround the tumor, and that a common type of immunotherapy could block this interaction and thus release MAIT cells to be cancer killers. In this illustration, some MAIT cells have been able to infiltrate a liver tumor (pink) and are hard at work destroying cancer cells, which can be seen bursting (red). Also shown are stromal cells (tan). Credit: Ruf, B., et al.; BioRender.com

Researchers have discovered that an enigmatic type of T cell in the liver can be effective at attacking liver cancer cells, but its anti-tumor activity is suppressed in some patients. At the same time, the investigators have shown how treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors can reverse this effect, helping this type of immune cell, called a mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cell, better attack and infiltrate liver tumors. The finding could explain why some patients with liver cancer, but not others, respond to treatment with immunotherapy.

T cells are a type of immune cell that play a critical role in protecting the body by attacking and killing harmful pathogens or cancer cells. MAIT cells are a subtype of T cells typically only found in the liver, gut or lungs, and are not well understood.

Senior Investigator Tim Greten, M.D., previously studied MAIT cells, and he was curious to understand the anti-tumor activity of these cells in the context of liver cancer, which remains difficult to treat and often involves a poor prognosis. His team used an array of detailed imaging techniques and RNA sequencing to analyze tissue samples from 37 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common type of liver cancer. Then they applied an artificial intelligence algorithm to help map out the function and location of MAITs, as well as neighboring cells.

“What makes this study distinct is that the tissue we analyzed contained the tumor, tumor rim and adjacent tissue, so we could actually study how the different cell types change from the tumor environment to the tumor,” explains Greten.

As they report in Cell, Greten, Staff Scientist Firouzeh Korangy, Ph.D., and their team were surprised to see that many MAIT cells surrounded the tumors — but did not infiltrate them as one would expect. In the environment around the tumors, the researchers also observed a high number of immune cells called macrophages adjacent to the defective MAIT cells that were unable to penetrate and attack tumors.

Macrophages are notorious for emitting signals that suppress the ability of immune cells to attack cancer via a signaling pathway called PD-1/PD-L1. A common type of immunotherapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors works by blocking these signals. Through a series of follow-up experiments in mice and human tissue samples, the researchers confirmed that the macrophages were emitting PD-1/PD-L1 signals, and that blocking these signals with immune checkpoint inhibitors could boost the ability of MAIT cells to attack tumors.

Additional experiments showed that tissue samples from humans who had been treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors had greater MAIT infiltration in their tumors, and similar results were found in mice.

“This study shows very clearly that these MAIT cells can exert anti-tumor immunity,” says Greten.

Based on these results, Greten says he is interested in exploring novel pathways beyond PD-1/PD-L1 that could be used to harness MAIT cells. He says, "Current therapy using immune checkpoint inhibitors only works in some patients. If we can find new therapies to boost MAIT cells, along with immune checkpoint inhibitors to better attack tumors, it could potentially lead to more effective cancer treatments."