Three-dimensional illustration of a T cell attacking a cancer cell.

Image credit: Meletios Verras/iStock

Researchers at CCR have discovered that a T-cell imbalance can trigger the rapid growth of a patient’s cancer following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, a phenomenon known as hyperprogressive disease. The finding, published September 28, 2022, in Cancer Immunology Research, is part of the first reported method to study hyperprogressive disease in an animal model.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have become a mainstay in cancer treatment. These drugs work by making tumor cells more susceptible to immune system attack. However, in some cases, immune checkpoint inhibition appears to suppress the immune system, and the tumors grow even faster than they did before treatment. This unexpected treatment outcome, which occurs in 10 to 25 percent of patients, is challenging to predict.

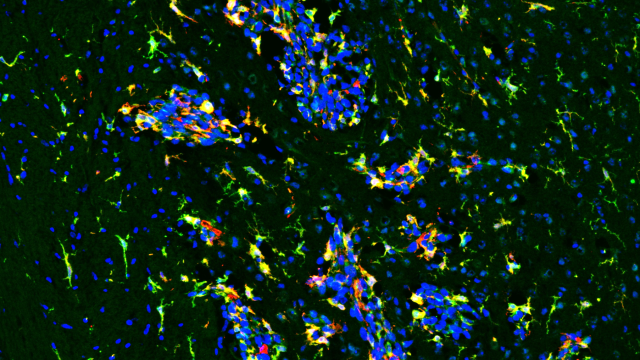

Previous studies have shown that biopsies from patients with hyperprogressive disease have a scarcity of cytotoxic T cells, but an abundance of regulatory T cells, in the tumor microenvironment. “This was compelling to us because cytotoxic T cells fight cancer, whereas regulatory T cells come to the tumor’s defense,” explains Hisataka Kobayashi, M.D., Ph.D., Senior Investigator in the Molecular Imaging Branch.

Kobayashi wanted to know if the imbalance between T cell types could cause hyperprogressive disease following immune checkpoint inhibition. Using a cutting-edge technique developed in his lab called near-infrared photoimmunotherapy (NIR-PIT), Kobayashi’s team partially depleted cytotoxic T cells in the tumor microenvironment in a mouse model of cancer. Only the mice with partially depleted cytotoxic T cells, and therefore an imbalance toward regulatory T cells, developed hyperprogressive disease following immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment.

“Ideally, cytotoxic T cells become more effective at fighting cancer with immune checkpoint inhibitors, but if those cells are overwhelmed by regulatory T cells, it appears the opposite occurs,” Kobayashi says. “Hopefully in the future, we can avoid this side effect in patients by carefully examining tumor biopsies for T-cell balance before starting treatment.”

The next step is to test if depleting or blocking regulatory T cells improves the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibition. “I don’t want to give any concerns to patients who are treated with checkpoint inhibitors — they can work very well,” Kobayashi emphasizes. “But some patients do suffer from hyperprogressive disease, and we want to understand why so that we can avoid this complication.”