A novel gene therapy approach proves safe and effective for children with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome.

Duy Anh “Harry” Le was just 2 months old, living in southern Vietnam, when his parents first noticed strange bleeding spots developing on his body. Doctors initially thought he had Dengue fever, but mysterious symptoms continued to emerge, including eczema and numerous infections. In April 2016, after months of exploring potential causes, a genetic test finally diagnosed Harry with WAS. The family moved to northern Vietnam in search of more information and treatments. “Harry was desperate. There was no treatment for him at that time,” explains Duy Le, Harry’s father, noting that his son was struggling to eat due to severe lesions in his mouth and digestive tract. Duy undertook a worldwide search for solutions at that point, eventually bringing his son to the U.S. in November 2016 to participate in Dr. Pai’s gene therapy clinical trial. After the trial, Harry’s symptoms improved dramatically, and he is now a happy and healthy 9-year-old with a broad smile. “The clinical trial, it's like a miracle. Now Harry can have a normal life, the same as other children,” says Duy. “I think it's really important for scientists to keep doing research like this, which is really, really helpful for children with rare diseases.”

Credit: Photo courtesy of Duy Le; SPGM, FNL, NCI, NIH; Adobe Firefly

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is a rare genetic disorder in which a mutation in the WAS gene hinders production of the WAS protein. This protein is critical for healthy white blood cell and platelet function, so people with WAS are at high risk of bleeding, eczema, infections, autoimmunity and lymphoma. Few patients live beyond the age of 15 without treatment.

WAS mainly affects boys because the gene is found on the X chromosome. Males only have one copy of the X chromosome, while females have two, and this second copy often compensates for the mutation on the other.

For decades, the standard treatment for WAS has been stem cell transplant from healthy tissue-type matched donors. However, immune-related complications and a lack of well-matched donors limit the success of this standard therapy.

Now, a clinical trial investigating a novel gene therapy for treating WAS shows that it is safe and can dramatically improve symptoms. Senior Investigator Sung-Yun Pai, M.D., launched and led the phase 1/2 clinical trial in five children with WAS while in her previous position at Boston Children’s Hospital, with her final analysis completed at CCR.

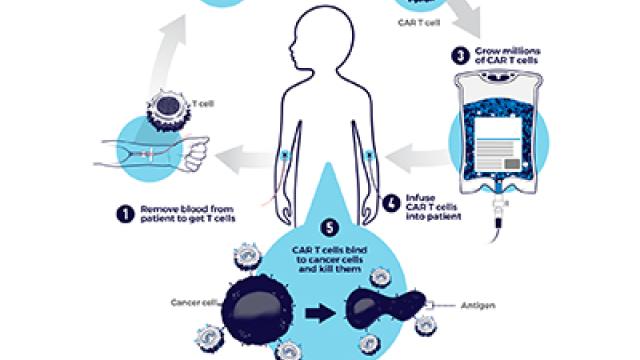

The therapy aims to add a functioning copy of the gene to the children’s own blood cells, avoiding immune complications from using a donor. A virus is used to insert the WAS gene into stem cells extracted from the patient, which are then reinfused back into the patient. With the gene added to their stem cells, patients were able to produce WAS protein in their white blood cells and platelets. Despite having below average levels of the protein after gene therapy, the significant reduction of symptoms in the patients suggests that enough WAS protein was being produced to be beneficial. The children had fewer infections and improved eczema, and there were no serious adverse events caused by the gene therapy itself. The results of the study were reported in Blood.

“We followed each patient for at least five years, and they did great. All of the patients had improvements in their immune system,” Pai notes. “Unhindered by their condition, they were able to act like kids again.”

Notably, when scientists use viruses to insert copies of a gene into cells, sometimes only one copy of a gene makes it into the cell. In this study, patients whose cells took up two copies of the WAS gene had platelet counts restored to essentially normal levels, while those with only one copy of the gene continued to have low platelets. Nevertheless, all patients had a reduction in severe bleeding.

The next step for Pai is to develop a more effective gene therapy for WAS that results in better protein expression and corrects platelet counts more effectively even if only one copy of the gene is inserted.

She emphasizes how important it is to continue doing research into rare diseases such as WAS, first and foremost to benefit patients. “Unless somebody takes an interest in their disease, they will never have better treatments,” Pai says, noting that research into genetic disorders also provides critical insights into the unknown underpinnings of disease biology.