Researchers pinpoint a critical protein in the liver that controls gut health and repair.

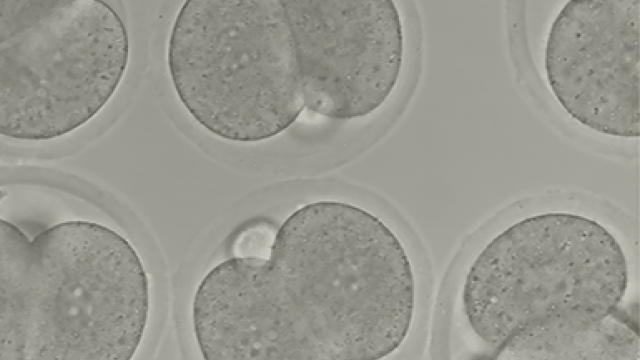

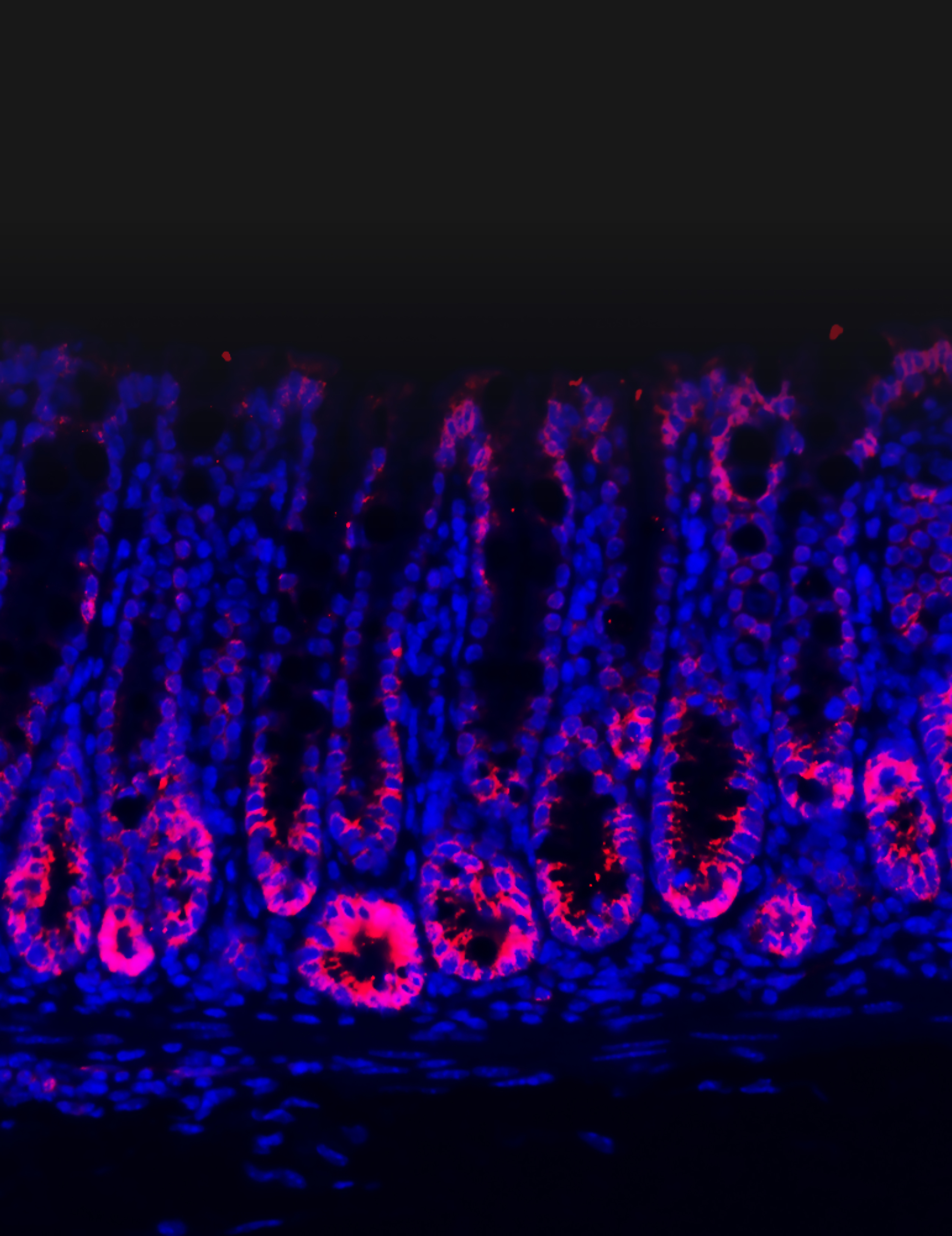

This image depicts intestinal tissues stained for PEDF protein (pink) from healthy mice. The liver produces PEDF, which binds to stem cells in the intestine and stops them from over-proliferating. When the intestines are damaged, they release signals that block PEDF production, liberating stem cell expansion to heal the gut.

Credit: Kim, G., et al.

The lining of the intestine is constantly exposed to a wide variety of microbes and food particles that can trigger immune responses and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a condition prevalent throughout the Western world.

Researchers have long known that activity between the liver and intestine is strongly interconnected, but knowledge about this phenomenon — called the gut-liver axis — has remained superficial for decades. This past year, CCR researchers dug deeper and detailed one element of this complex connection in unprecedented detail.

They identified an important protein in the liver that helps keep intestinal stem cell division in check, influencing health in the gut. The results, published in Cell, hold important implications for intestinal conditions, like IBD, and potentially for cancer.

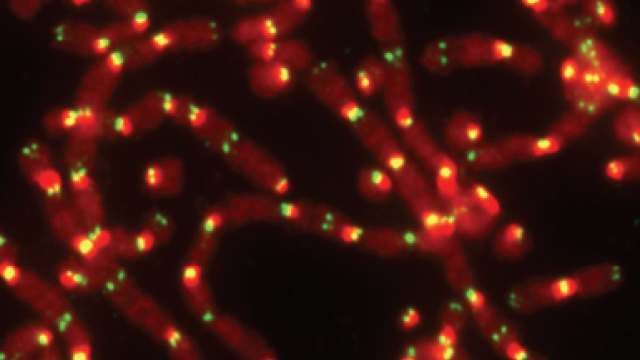

Stem cells are precursor cells that can turn into various types of cells as needed. If the lining of the gut is damaged from inflammation, stem cells in the area can start dividing and replacing damaged cells. However, too much cell division can be associated with cancer.

As Senior Investigator Chuan Wu, M.D., Ph.D., was studying the livers of mice to better understand the organ’s role in maintaining gut health, he observed an unexpectedly dramatic result. Removing part of the liver caused a significant spike in the production of stem cells in the intestines.

“It was the most striking result you can observe after you perform such an experiment, so we became interested in studying these stem cells in greater detail,” explains Wu.

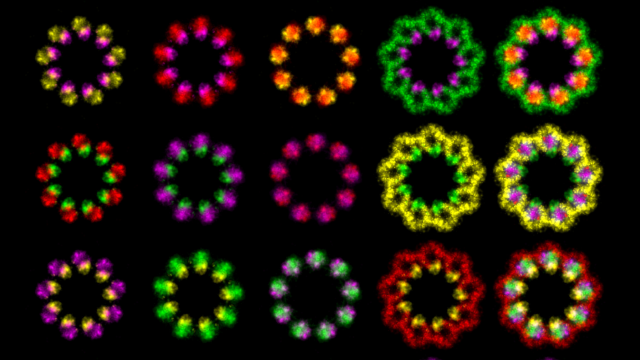

Through a series of intricate experiments in healthy mice and mice with gut disease, the team showed how a protein called pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is released from the liver and controls stem cell division in the gut, ensuring that stem cells do not proliferate excessively. When PEDF production is reduced, these stem cells start to multiply. This is why removing part of the liver — and thus PEDF — caused such a spike in intestinal stem cell production.

The connection between the gut and liver is like a two-way street, the researchers found. Damaged intestines will release danger signals to the liver, repressing production of PEDF via a protein called PPAR-alpha. This, in turn, releases the hold on stem cell expansion in the gut, allowing the stem cells to grow and heal the inflamed tissue.

Sure enough, in mice with inflamed guts, the researchers found that inhibiting PEDF could alleviate their symptoms. “These results may actually give us an idea of how vital liver function is for IBD patients,” Wu emphasizes.

The research team also looked at data from people, which suggests that similar mechanisms are at play within our bodies. In fact, the findings of this study may explain why a cholesterol drug called fenofibrate, which activates PPAR-alpha, has been associated with intestinal inflammation in humans.

Given that intestinal stem cells are important for both inflammation and tumor development, the research by Wu and his colleagues may also help shed light on how PEDF influences colon cancer on a molecular level.