A personalized approach to cellular immunotherapy helps shrink solid tumors.

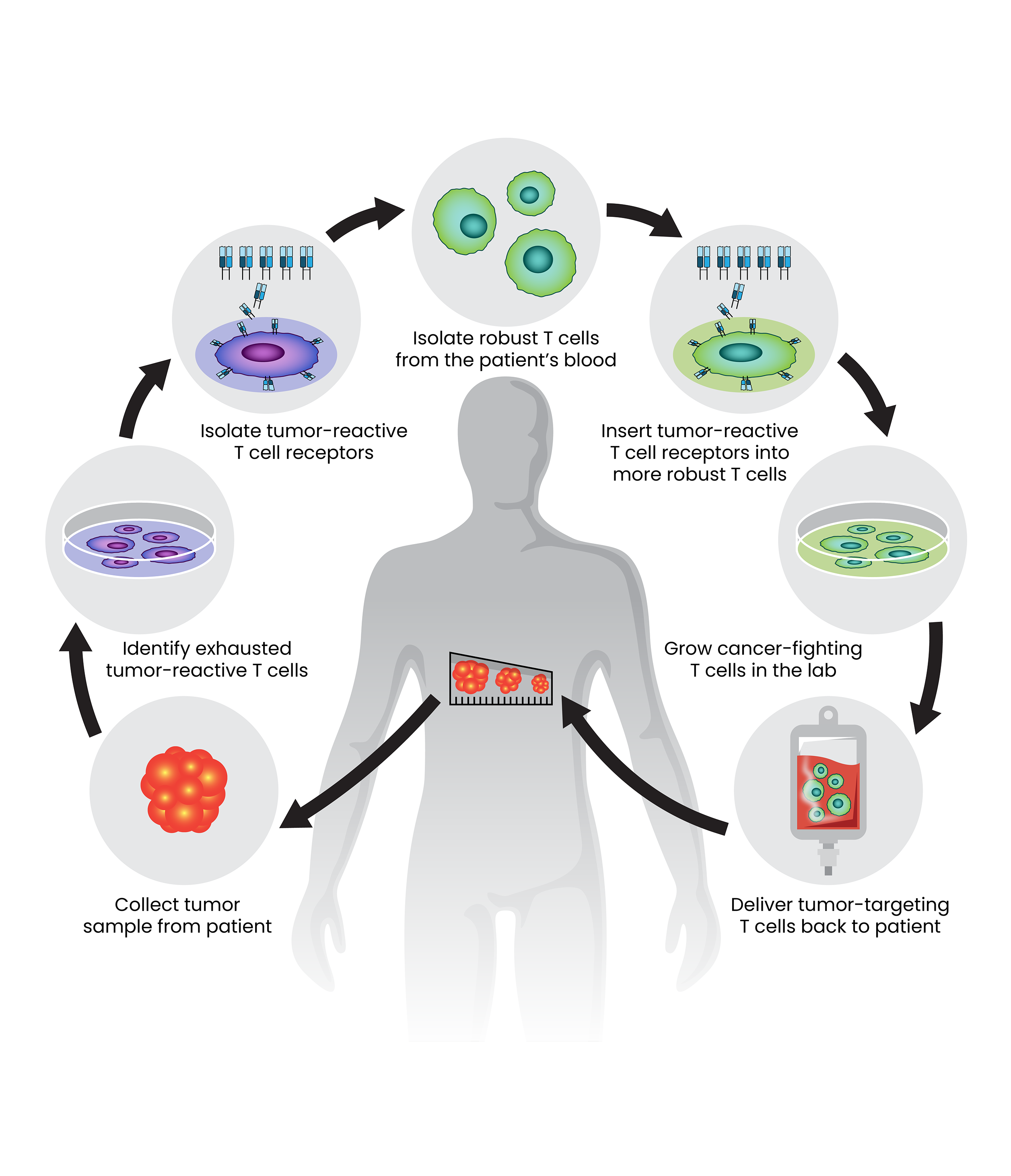

A new approach to cellular immunotherapy, outlined here, holds promise for patients with solid epithelial cancers. The treatment is highly personalized. It combines T-cell receptors that can identify the specific mutations of the patient’s tumor with robust T cells from the patient’s blood to attack the cancer.

Credit: SPGM, FNL, NCI, NIH

More than twenty years ago, scientists showed that it is possible to reprogram patients’ own immune cells to fight their cancer. Cellular immunotherapies are now important tools for fighting cancer, and CCR scientists are working to extend their reach.

While cellular immunotherapies are effective against many blood cancers and melanomas, other kinds of solid tumors have been mostly unresponsive to this type of treatment. But in an ongoing clinical trial led by Steven Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., researchers have found that with a new approach, patients’ immune cells can be programmed to shrink metastatic colon cancer, too.

“The methodology that we've developed works,” says Rosenberg, whose group at NCI has pioneered these innovative types of treatments for decades. “We're concentrating now on solid epithelial cancers — common cancers that occur in the solid organs of the body. Ninety percent of everyone who dies of cancer dies of these. This is the beginning of a new way to use immunotherapy.”

The success, reported in Nature Medicine, comes from a phase 2 clinical trial in which Rosenberg and colleagues are reprogramming healthy T cells from patients’ blood to recognize and attack their cancer cells. They are using an approach that Rosenberg says can be used to generate personalized tumor-reactive T cells for many cancer types. The trial is open to patients with metastatic solid cancers including gastrointestinal, breast, lung and endocrine cancers.

Rosenberg’s group has found that most patients with cancer already have naturally occurring T cells that can recognize mutations that distinguish their tumor cells from healthy cells. However, once these T cells infiltrate tumors, they encounter a hostile, immune-suppressing environment. As a result, most of the T cells found inside tumors are too exhausted to destroy their targets or rally additional immune defenses.

To address this issue, Rosenberg’s team, led by Staff Scientist Maria Parkhurst, Ph.D., collected T cells from inside the tumors of each patient in their clinical trial, then isolated the receptors that those cells used to recognize the cancer.

Parkhurst then introduced those tumor-targeting receptors onto more robust T cells from the same patient’s blood. The reprogrammed cells were grown in the lab, generating enormous numbers of healthy, cancer-fighting cells to deliver back to the patient.

This approach differs from CAR T-cell therapy, which uses engineered receptors to direct T cells to their targets and was first reported in patients by Rosenberg’s group in 2010. CAR T-cell therapy is used to treat certain kinds of blood cancer by targeting normal molecules overexpressed on the cancer and shared across patients. A more personalized approach is needed for solid cancers, where the tumor-specific mutations that activate the immune system are much more diverse and are largely patient specific.

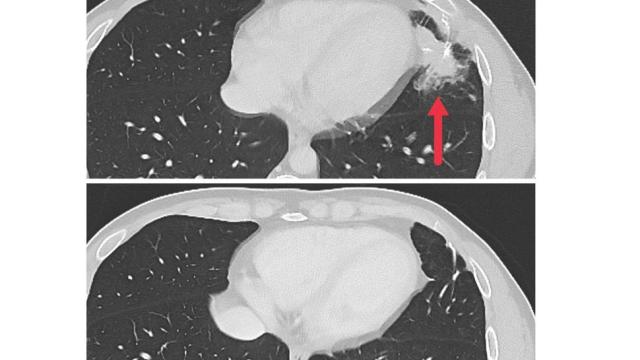

The early results of the clinical study focused on seven participants with metastatic colon cancer. All had undergone multiple cancer treatments prior to entering the study, and their cancers had continued to grow. After the experimental immunotherapy, tumors shrank for three of the patients, and regrowth was kept at bay for four to seven months.

Although the trial is ongoing and the results are preliminary, they are encouraging. “Cancer immunotherapy is already having an important impact,” Rosenberg says. “I think it represents the most exciting area of research that has the potential to develop effective treatments for patients with metastatic cancer.”