Inhibiting an enzyme in the growth-promoting Ras pathway could stop the childhood cancer rhabdomyosarcoma.

This wind-rose plot taken from the study shows that MEK inhibitors are potent and selective for fusion-negative rhabdomyosarcoma as compared to fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma and normal cell lines. Each cell line investigated corresponds to a spoke of the plot.

Credit: Berkley Gryder, CCR, NCI, NIH

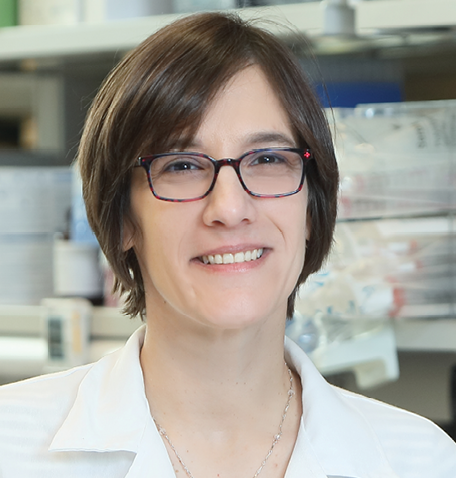

CCR scientists have uncovered a potential new treatment strategy for rhabdomyosarcoma, a rare cancer that occurs mostly in children and arises from muscle progenitor cells that never properly mature. Their studies may lead to better options for patients with the disease who often experience severe side effects from chemotherapy.

Investigators Marielle Yohe, M.D., Ph.D., in CCR’s Pediatric Oncology Branch and Javed Khan, M.D., in CCR’s Genetics Branch, explored how mutations in the Ras family of genes, cancer-driving mutations that are present in about a third of human tumors, influence the growth of rhabdomyosarcoma. Their studies, published in Science Translational Medicine, suggest that blocking a protein in the Ras signaling pathway known as MEK may be an effective treatment for the subset of rhabdomyosarcomas that are driven by Ras mutations.

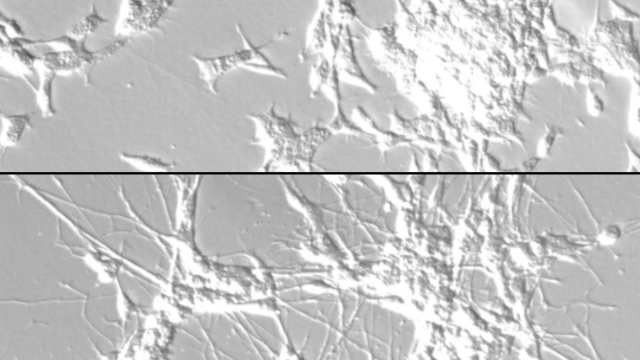

The team screened more than 1,900 drugs and found those that inhibited MEK signaling, including the FDA-approved cancer drug trametinib, dramatically slowed the growth of Ras-driven rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Cancer cells treated with trametinib not only stopped dividing, they began to take on the characteristics of more mature muscle cells, losing key features of the precursor cells, or myoblasts, from which rhabdomyosarcoma develops. When the team administered trametinib to mice with rhabdomyosarcoma tumors, they saw similar effects: cancerous myoblasts began to mature, and tumor growth slowed. In their experiments, mice treated with trametinib lived longer than those that did not receive the drug.

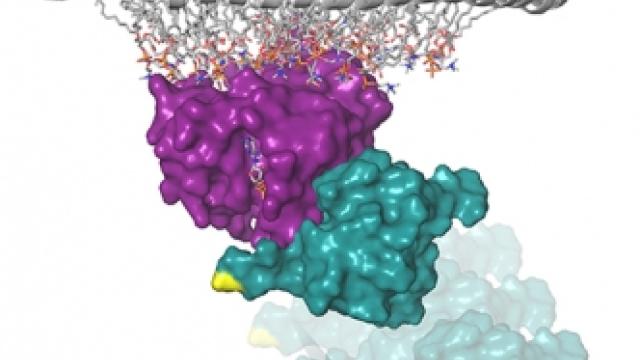

Yohe’s team also conducted detailed experiments to reveal exactly how Ras and MEK affected muscle differentiation. They found that an enzyme activated by MEK called ERK2 not only switches on genes involved in cell division, it also keeps a gene called MYOG, which helps orchestrate myoblasts’ transformation to more mature muscle cells, turned off.

Although these results were encouraging, the team found that rhabdomyosarcoma cells quickly developed resistance to trametinib. With a second drug screen, this time testing nearly 600 combinations of drugs, the researchers found that they could generate a more potent and prolonged response by combining trametinib with a compound called BMS-754807. Based on these findings, Yohe and her colleagues are now exploring the potential of combining trametinib with a BMS-754807-like drug to treat Ras-driven rhabdomyosarcoma in patients.

Yohe says that apart from its potential to reduce tumor growth, MEK inhibition might also be useful as a maintenance therapy to promote differentiation of any cancer cells that remain after patients with rhabdomyosarcoma complete chemotherapy.