A compound that reduces the prevalence of an enigmatic cellular structure linked to metastasis blocks the spread of cancer in animals.

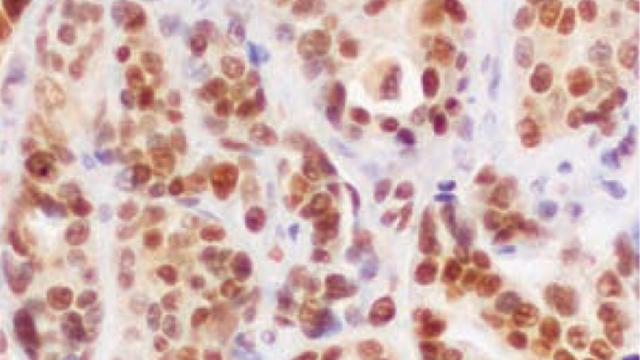

In the upper image, an electron micrograph at 1,000x magnification depicts the nucleus (with a thin, dark outline) of a metastatic human cancer cell with three nucleoli. Structures within the nucleoli actively fuel metastasis. In cells treated with metarrestin, like the one below, the nucleoli collapse, becoming highly dense, and develop a nucleolar ‘cap’ formation. While the nucleus and other components of the cell remain intact, the nucleoli are now unable to promote metastasis.

Credit: Kunio Nagashima, CCR, NCI, NIH

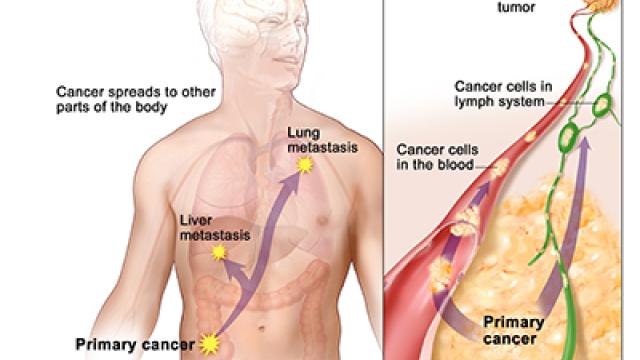

Metastasis, the spread of cancer cells from a primary tumor to other parts of the body, is the cause of most cancer-related deaths. Finding an effective way to interfere with this complex process holds tremendous benefit for patients with a broad range of cancer types, but so far, there are no approved cancer therapies that specifically target metastatic cells. CCR scientists, in collaboration with researchers from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) and Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, have now identified an experimental drug that may arrest metastasis.

In this decade-long collaboration, researchers have identified and tested a potential anti-metastasis drug that they call metarrestin. Led by Udo Rudloff, M.D., Ph.D., Investigator in the CCR Pediatric Oncology Branch, the CCR team showed that metarrestin prevents different implanted human tumor types from metastasizing in animals and significantly extends the lives of mice bearing aggressive human tumors. Their findings were published in Science Translational Medicine.

Metarrestin drew the researchers’ attention because of its potential to eliminate a poorly understood subcellular structure that is found in cancer cells and not in normal cells. Under a microscope, that structure, known as the perinuclear compartment (PNC), appears as a tiny speck inside a cell’s nucleus. The exact function of this tiny compartment remains unknown, but researchers do know that the more PNCs cancer cells have, the more likely they are to metastasize.

PNCs are such reliable indicators of a cancer cell’s metastatic potential that the team hoped they might be able to use them to find a drug that stops metastatic cells in their tracks. Scientists at NCATS conducted a massive drug screen to find compounds that make PNCs disappear. After devising an automated microscopy method to assess the presence of PNCs in individual cells, they tested how their prevalence changed when metastatic cancer cells were exposed to each of about 140,000 potential small-molecule drugs. The most promising compound from the screen was chemically modified and improved to use as a drug to further enhance its PNC-reducing effects. The resulting compound was named metarrestin.

Experiments in Rudloff’s lab yielded encouraging results. Metarrestin did not just reduce the number of PNCs in cancer cells and keep metastatic cancer cells from growing in laboratory dishes. It also blocked tumor metastasis in mouse models of cancer. Whereas untreated animals developed metastatic tumors in the livers and lungs, these organs were nearly tumor-free in mice that were treated with metarrestin. Mice with metastatic pancreatic tumors that were treated with metarrestin lived significantly longer than untreated animals. Many animals were considered cured if no disease developed after six months.

Rudloff and his colleagues are now preparing to evaluate metarrestin’s effects in patients with metastatic cancers. The team hopes to launch an initial first-in-human trial of metarrestin at the NIH Clinical Center in 2019.