A variation of a once-banned drug proves effective for patients living with AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma.

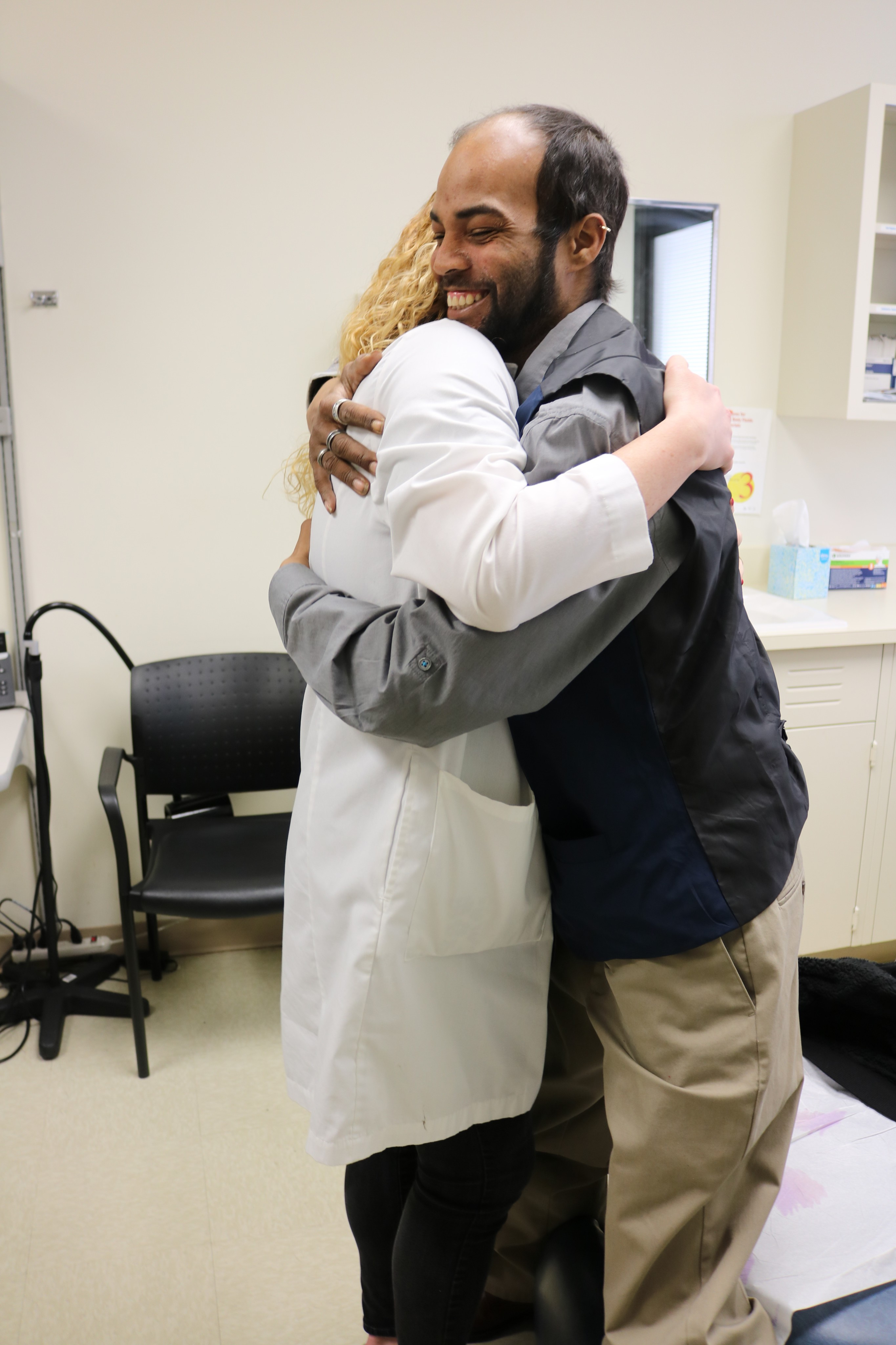

Patient Brandon Lutrell greets Dr. Kathryn Lurain. Lutrell is a patient on the HIV and AIDS Malignancy Branch service with Kaposi sarcoma who has received pomalidomide. This photo was taken in March 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Credit: Lianne Priede, Center for Cancer Research, NCI, NIH

First marketed in the late 1950s, thalidomide was widely prescribed to pregnant woman as a sedative to relieve morning sickness until tragedy struck. Although never approved in the United States, the drug was banned worldwide in the 1960s after thousands of babies were born with deformed limbs. Remarkably, since then, the drug has emerged as a treatment for leprosy as well as multiple myeloma.

Now, CCR investigators have shown that a derivative of thalidomide, known as pomalidomide (Pomalyst®), can treat Kaposi sarcoma, a rare cancer that grows on the skin as well as in lymph nodes, lungs and other regions of the body. In the U.S., about 2,000 people per year are diagnosed with the disease. Immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV, are most at risk.

In May 2020, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) expanded the indication of pomalidomide. The expansion includes treatment of adult patients with AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma that have not responded to highly active antiretroviral therapy as well as initial treatment of HIV-negative adult patients with Kaposi sarcoma. The approval was based on findings of a phase I/II clinical trial led by Robert Yarchoan, M.D., that started enrollment in 2012.

Kaposi sarcoma patches consist of a class of blood vessel cells, known as endothelial cells, that grow uncontrollably. Yarchoan and his team hypothesized that thalidomide, which blocks blood vessel formation, could impact the disease. Their research showed that AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma patients responded to thalidomide, but the side effects, which included fatigue and depression, outweighed the benefits, Yarchoan says.

Meanwhile, Yarchoan and his team had grown interested in less toxic derivatives of thalidomide, which led them to pomalidomide. In collaboration with Celgene Corporation, now Bristol-Myers Squibb, they tested pomalidomide in Kaposi sarcoma in this phase I/II trial under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement.

The trial ultimately led to FDA approval of pomalidomide for the treatment of Kaposi sarcoma. It enrolled 18 HIV-positive and 10 HIV-negative patients. Twelve of the HIV-positive patients had a complete or partial response to pomalidomide, which lasted an average of about one year. Eight of the HIV-negative patients had a complete or partial response, which lasted slightly less than a year, on average. In both groups, pomalidomide increased the number of T cells, an important class of immune cells destroyed by HIV. The treatment was well-tolerated, with relatively minor side effects, such as skin rash, vomiting and diarrhea.

Pomalidomide provides Kaposi sarcoma patients with a treatment option that is not only less toxic than chemotherapy, but also easier to administer. While other systemic drugs used to treat this cancer are delivered intravenously, pomalidomide is given orally, making it a more feasible option for people living in lower- and middle-income countries. The global AIDS Malignancy Consortium supported by NCI has recently begun testing pomalidomide for Kaposi sarcoma in Africa, where the disease is especially prevalent in young men.