A drug routinely used to prevent the adverse effects of bone marrow transplantation works differently than widely thought.

Rut Perez-Romero was pregnant with her first child when she was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Chemotherapy sent her into remission, and her son is now a healthy nine-year-old. A 2014 relapse was successfully treated, but in January 2019, Perez-Romero learned that the cancer had returned, and she was pregnant again. Given the circumstances, she received safer, more conservative chemotherapy drugs and delivered a healthy son, who is now 10 months old. With help from her doctors, she next identified and enrolled in Kanakry’s clinical trial to receive a bone marrow transplant. Her risks for GVHD, particularly chronic GVHD, were lowered substantially by the inclusion of cyclophosphamide in her GVHD prophylaxis. She has not had any GVHD in the seven months since transplant.

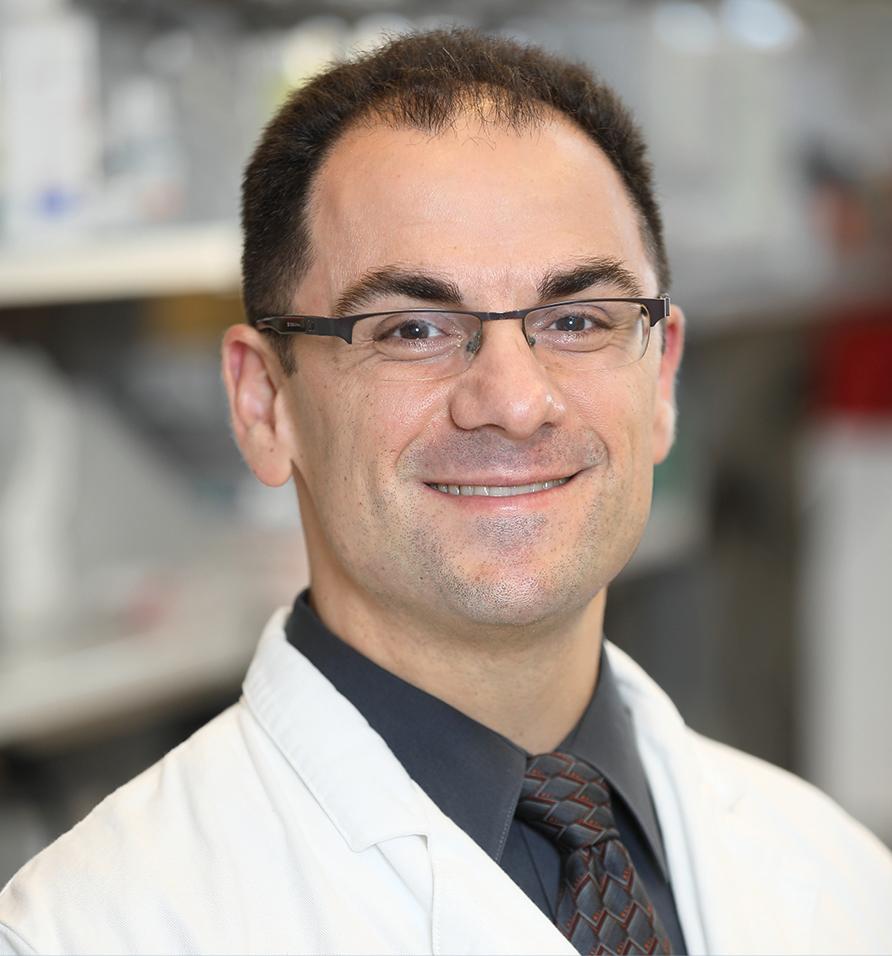

Credit: Leslie E. Kossoff, LK Photos

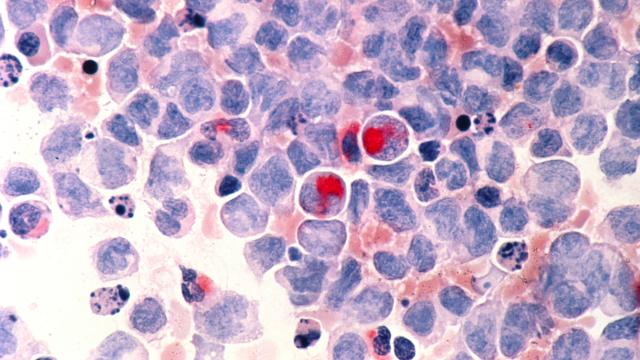

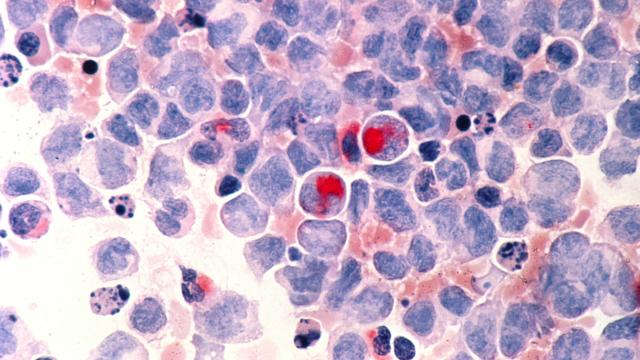

Many patients with advanced blood or bone marrow cancers have no choice but to undergo treatment with a bone marrow transplant. However, the procedure carries the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), a potentially fatal condition in which the immune cells in the transplant view the recipient’s body as foreign and mount an attack against it.

To prevent GVHD, transplant recipients can be treated early after transplant with a drug called cyclophosphamide. This commonly used drug has long been thought to work by eliminating the disease-fighting T cells that turn against the recipient’s body. Research led by Christopher G. Kanakry, M.D., and published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, challenges this theory, suggesting that cyclophosphamide impairs the function of these T cells rather than eliminating them.

In the 1990s, studies in skin grafts in mice reported that cyclophosphamide eliminated the T cells that respond to the transplant. Since then, this has been the accepted mechanism for how the drug prevents GVHD in bone marrow transplant patients. However, this model does not square with clinical observations. Up to 80 percent of patients experience low-to-intermediate grade acute GVHD, despite undergoing cyclophosphamide treatment, which should not occur if the drug eliminates the T cells that cause GVHD.

Kanakry and his team investigated the effects of the drug in mice that had undergone bone marrow transplantation. They found that the percentages of T cells reactive to the recipient were roughly equal to or greater in cyclophosphamide-treated mice than in untreated mice. They also saw that these recipient-reactive donor T cells isolated from mice treated with cyclophosphamide had a dampened immune response when cultured with host cells. In addition, when they were infused into new recipient mice, the result was lower-grade GVHD than with donor T cells isolated from untreated mice.

Christopher G. Kanakry, M.D.

Lasker Clinical Research Scholar

Experimental Transplantation and

Immunotherapy Branch

The results suggest that the drug does not eliminate T cells but impairs them enough to prevent them from causing severe GVHD while still potentially allowing them to trigger lower-grade acute GVHD, consistent with clinical observations. Now, the Kanakry laboratory is investigating the specifics of how the drug impairs the T cells. He thinks that understanding how cyclophosphamide prevents GVHD will potentially allow for the rational development of new strategies that could later improve outcomes for patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation and could have relevance for other types of tissue transplants as well as autoimmune diseases.

Kanakry notes that the protective environment of CCR, which nurtures high-risk research, was critical to being able to steadily pursue these studies that challenge a widely accepted theory.