New advances suggest opportunities to treat a broadening range of cancers with cell-based immunotherapies.

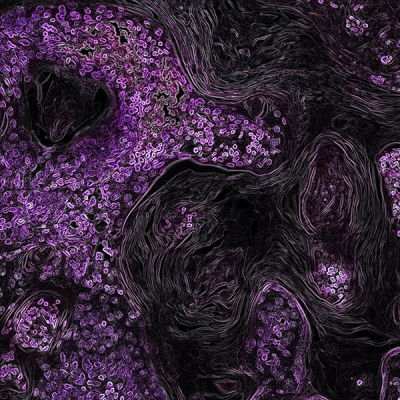

In this image from a genetically engineered mouse model, lung cancer driven by the KRAS oncogene shows up in purple. As a key driver in many types of cancer, the KRAS gene makes a promising target for new cancer therapies.

Credit: NCI, NIH

CCR scientists have long led the way in developing and testing immunotherapies, which strengthen patients’ immune systems to confront their cancers head-on. Now, building on decades of laboratory and clinical findings, they are working to improve these revolutionary therapies and expand their potential.

Two recent advances highlight new opportunities. One, reported in the New England Journal of Medicine by a team led by Steven Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., Chief of CCR’s Surgery Branch, is the successful treatment of a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer using adoptive cell therapy (ACT). In ACT, a patient’s own cancer-fighting immune cells are grown in the laboratory and then returned to the patient in larger numbers, bolstering the body’s defenses.

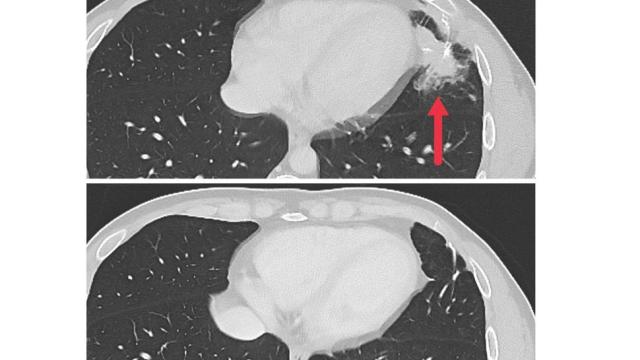

An exciting aspect of this success is that the immune cells used for the treatment target cells with a mutation in a gene called KRAS. KRAS mutations are thought to drive the growth of 45 percent of colorectal cancers and 95 percent of pancreatic cancers. The specific mutation targeted in this study is estimated to occur in more than 50,000 new cancer cases in the United States each year.

Researchers have struggled for decades to develop therapies that rein in mutant forms of Ras proteins, but they have proved elusive targets. Now that Rosenberg’s team has shown KRAS-targeting immune cells can lead to tumor regression in a patient with advanced disease, they hope this strategy can be used to treat other cancers with the same mutation.

CCR scientists are also exploring ACT as a treatment for cancers caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). In 2015, a team led by Rosenberg and Christian Hinrichs, M.D., an Investigator in CCR’s Experimental Transplantation and Immunology Branch (ETIB), reported in the Journal of Clinical Oncology some success in a clinical trial for patients with advanced cervical cancer.

For two of the 18 women in that trial, ACT caused complete and lasting tumor regression. Now, Hinrichs and his colleagues have taken a closer look at the immune cells responsible for their recoveries and made a surprising discovery.

Women in the trial were treated with cancer-fighting immune cells that had been isolated from their own tumors and multiplied in the laboratory. Although the mixtures of cells selected for the treatment were chosen because they were particularly adept at targeting tumor cells bearing markers produced by HPV, the new analysis revealed that the dominant anticancer cells in their systems do not target HPV-specific antigens. Instead, they are sensitive to antigens produced due to mutations in the tumors’ own genomes. The findings, published in Science, have important implications for the design of new cellular immunotherapies—not just for HPV-associated cancers but potentially for others as well.

The team found that a non-viral antigen that seemed to trigger a strong response against one patient’s cervical cancer is produced by about 40 percent of cervical cancers. Other researchers have reported that the same antigen is found in many breast, lung and stomach cancers, raising the possibility that a therapy targeting this antigen could be effective for many cancer types.

Lasting Immunotherapy Success in Lymphoma Patients

CCR scientists also continue to follow patients who have responded well to existing treatments. The longest follow-up to date of patients who have received chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, a treatment that modifies a patient’s T cells in the laboratory to better recognize and eliminate tumor cells, was reported in Molecular Therapy. The study, led by ETIB Investigator James Kochenderfer, M.D., and Dr. Rosenberg, focused on patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphomas who received experimental treatment at the NIH Clinical Center. Five of seven patients in that study experienced complete remissions following treatment. Three years later, four patients’ cancers remain in remission. The long-lasting responses raise the possibility that a single treatment with CAR T-cell therapy can be curative for this aggressive blood cancer.

Kochenderfer J, et al. Molecular Therapy. 2017 October (10): 2245-2253.

Reference

Stevanović S, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2015 May (14):1543-50.

Tran E, et al. NEJM. 2016 December (375):2255-2262.

Stevanović S, et al. Science. 2017 Apr 14;356(6334):200-205.