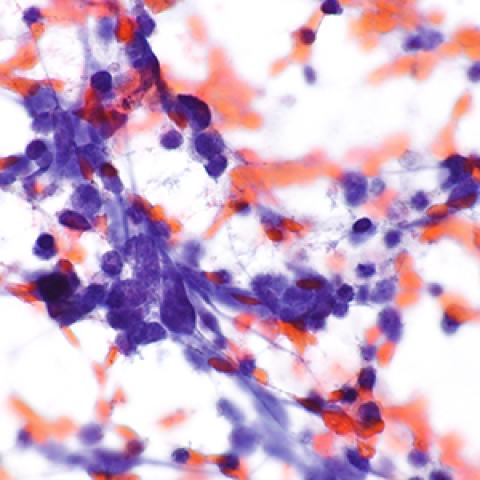

Micrograph showing small cell carcinoma of the lung

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Certain inherited mutations increase an individual’s risk of developing small cell lung cancer, an aggressive form of lung cancer, according to a new study from CCR scientists. However, patients with the disease who harbor these mutations may be more likely than others to respond to therapies that exploit defects in DNA repair pathways; they also appear to have a better prognosis when treated with a standard chemotherapy regimen. The findings, reported January 27, 2021, in Science Translational Medicine, could help clinicians identify the best individualized treatments for the disease.

The genetic factors that influence small cell lung cancer risk have not received a great deal of attention from scientists, because their impact on cancer susceptibility is overshadowed by the influence of tobacco exposure, says Anish Thomas, M.B.B.S., M.D., Lasker Clinical Research Scholar in CCR’s Developmental Therapeutics Branch. But when Thomas and his colleagues encountered a patient with a strong family history of small cell lung cancer, they became interested in potential genetic factors that might make people especially susceptible to the disease.

To investigate, they examined the sequences of more than 600 genes in the non-cancerous cells of 87 patients with small cell carcinomas. They found hereditary mutations that are known to increase cancer risk in about 10 percent of these patients. These mutations disrupted the function of various DNA repair genes, including many known to significantly increase the risk of other cancers, such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and RAD51D. When the team looked for these mutations in a second group of patients, they found them in a similar proportion of people.

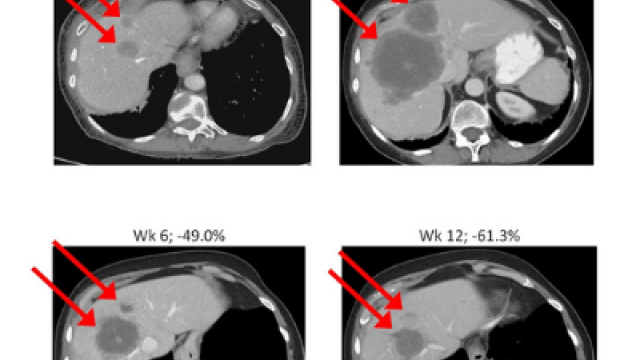

Patients with inherited mutations had their disease stay in remission longer following standard platinum-based chemotherapy than patients without mutations who received the same treatment. They were also more likely to have had a close relative who developed cancer.

The findings suggest that patients with these mutations could benefit most from chemotherapies that exploit cancer cells’ inability to repair damaged DNA. They also indicate that therapies that target cells with specific defects in DNA repair, which are approved for use in several kinds of cancer, may be beneficial for a subset of patients with small cell lung cancer.

Currently, all small cell lung cancer patients receive the same treatment. Thomas says his team’s findings are a first step toward potentially changing clinical practice and a more tailored approach to treatment selection. “We need to study larger cohorts of patients to see if this holds true,” he says. “If it does, the treatment of small cell cancers may follow paradigms similar to ovarian cancer and breast cancer, where inherited mutations are routinely looked at and influence how we treat patients.”