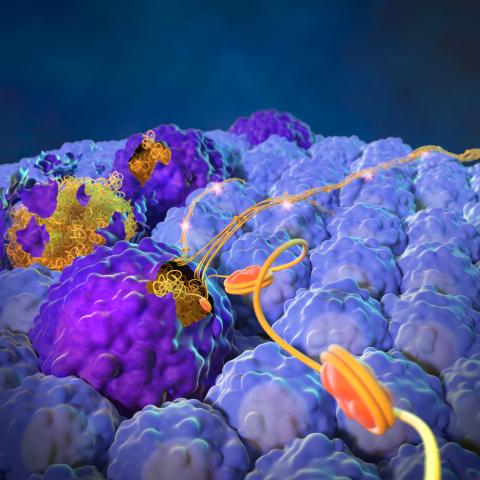

Cancer cells that die via apoptosis (larger dark purple structures) expel their nuclear contents (orange and yellow stringy structures) to spur metastasis and growth of living cancer cells (smaller light blue structures). Image credit: Yang Lab

When cancer cells die, they leave behind signals that spur the growth of the cells they’ve left behind, according to a new study led by Li Yang, Ph.D., Senior Investigator in the Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics. The discovery, reported March 27, 2023, in Nature Cancer, suggests that blocking those signals could reduce the likelihood that cancer will recur after treatment.

Yang says her team’s findings highlight the fact that individual cancer cells are part of a community of cells whose members influence one another’s behavior — even in their final moments. Within cancer cell communities, she says, death is commonplace. Once metastasizing cells leave a primary tumor, they encounter a hostile environment that most can’t survive. And when a patient undergoes cancer treatment, the number of dying cancer cells in the body rises still further. Usually, however, some tumor cells persist — and may change their behavior in response to other cells’ deaths. “It’s almost like dying tumor cells give some sort of last words to the live tumor cells so those cells can survive better,” Yang says.

To investigate this, Yang and her team, including postdoctoral fellow Woo-Yong Park, Ph.D., and graduate student Justin Grey, focused on cells that die through a process known as apoptosis. Various stressors that cancer cells naturally encounter in the body can trigger apoptosis. So too can cancer treatments like radiation and chemotherapy.

The researchers’ first step was to watch cancer cells under a microscope as they underwent apoptosis. Collaborating with Steven D. Cappell, Ph.D., Stadtman Investigator in the Laboratory of Cancer Biology and Genetics, who applies state-of-the-art live-cell imaging approaches in his cell cycle research, they saw the nuclei of dying cells swell dramatically and then burst, spewing their DNA and other contents into their surroundings.

In mice, Yang’s team found that the contents released from burst nuclei triggered growth-promoting signaling in nearby mammary tumor cells and accelerated the growth of metastatic tumors. They traced these effects to a molecule called S100a4, which clung to protein-wrapped strands of DNA called chromatin.

The team suspects apoptotic cells may also help drive the growth of metastatic tumors in humans. In an analysis of tumor samples from patients with breast or lung cancer, they found that outcomes tended to be worse when the genetic activity of patients’ tumors indicated a high level of apoptosis-induced nuclear expulsion.

The team has identified the molecular pathway that cancer cells use to detect and respond to the signals released by dying cells. They say it may be possible to block those signals to prevent cells that die during cancer therapy from provoking the growth of any cancer cells that remain.