3D structure of a melanoma cell.

Photo courtesy of NIH Flickr

Based on mouse models, CCR researchers have found that the genetic diversity of mutations in a melanoma tumor may be a critical factor in why some melanomas respond better to immunotherapy than others. The results appeared September 12, 2019, in Cell and hint at which melanoma patients could benefit from immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy involves techniques that boosts the ability of a patient’s immune system to identify and attack cancerous cells. But as Eytan Ruppin, M.D., Ph.D., of CCR’s Cancer Data Science Laboratory, notes, “Immunotherapy only works in some patients, even in melanoma, among its current best success stories. So naturally the question of why some patients respond well, while others don’t, is highly important.”

One way of identifying tumors that may respond well to therapy is to look at how many genetic mutations are in a tumor – its mutational load. Even though tumors with higher mutational loads tend to respond better, this is not always the case.

Evidence over recent years, however, suggests that another factor may be at play, in particular the diversity level of mutations in a tumor, referred to as intratumor heterogeneity, or ITH.

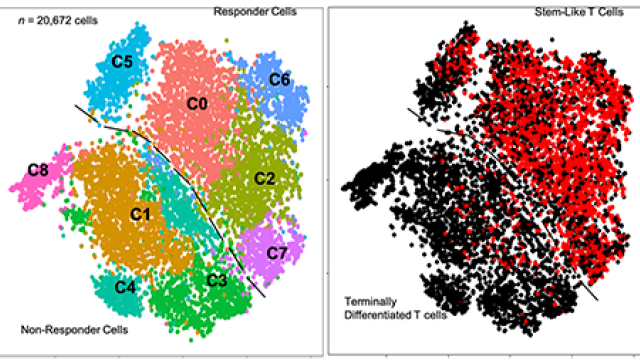

To study the effect of ITH independently from mutation load, Ruppin and his colleagues partnered with Yardena Samuels’ lab at the Weizmann Institute in Israel. They took a population of melanoma cells exposed to UV radiation and created a series of clones from the cell line. This gave rise to a collection of cancer cell populations with different combinations of low and high ITH as well as low and high amounts of mutational load.

Their results showed that tumors with low ITH did not grow significantly when implanted in mice, whereas tumors with high ITH did regardless of mutational load.Notably, mice with the low-ITH tumors showed a stronger immune response and were capable of rejecting the tumors in some cases while high-ITH tumors did not elicit an effective immune response, even while carrying the same overall mutational load as the low ITH tumors.

To understand whether similar results could occur in humans, the researchers, led by Sushant Patkar from Ruppin’s lab, analyzed human melanoma tissue data from The Cancer Genome Atlas program and other immunotherapy datasets by ITH level.

“Overall we found that tumor ITH is a very important determinant of patient survival and response to immunotherapy. The higher the ITH of the tumors, the worse the response,” says Ruppin.

Next, his team plans to extend this study of ITH to other cancer types to determine whether these findings are more widely applicable. Together with the Samuels lab, they also hope to gain a better mechanistic understanding of how increased tumor ITH hampers the immune response to tumors.

“This is of considerable importance to developing future, better immunotherapy treatments,” Ruppin says.