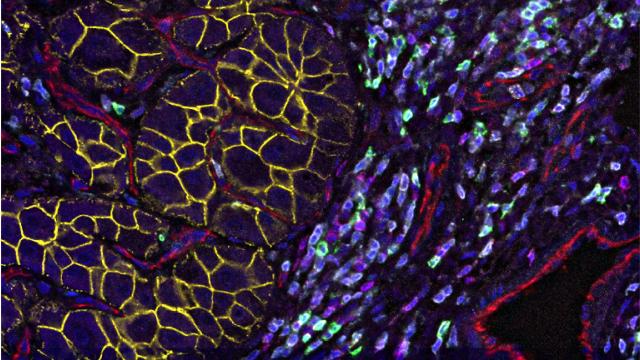

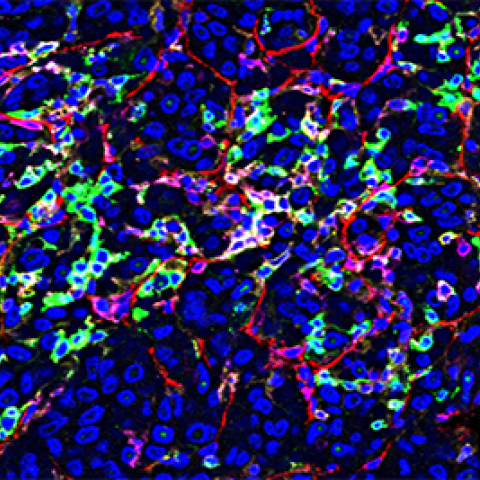

Single-cell immune profiling reveals distinct heterogeneity and spatial organization of a hepatocellular carcinoma tumor stained using Co-Detection by indexing (CODEX) technology.

Image Credit: Subreen Khatib

Researchers at CCR studying liver cancer have identified a protein that may drive tumors to evolve and evade therapy. This finding may help answer a major question in cancer research that revolves around what factors cause some tumors to evolve and become more aggressive despite treatment. The finding could also lead to new therapies for patients who do not respond to treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors, a type of therapy that has shown some promise in only a small subset of patients with this difficult-to-treat cancer. The study appeared June 30, 2021, in the Journal of Hepatology.

It is well known that tumor cells with more genetic mutations, and thus more diverse proteins present on their surfaces, tend to be more aggressive and persist despite treatment with anti-cancer drugs. This is especially true for two forms of liver cancer called hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA).

Researchers are keen to know what causes cancers like these to develop. Factors may include a diversity of mutations and resultant proteins, known as heterogeneity. Xin Wei Wang, Ph.D., Deputy Chief of the Laboratory of Human Carcinogenesis, has been studying this phenomenon in liver cancer for 18 years. In his recent work, Wang, along with his collaborators including Tim F. Greten, M.D., Deputy Chief of the Thoracic and GI Malignancies Branch and co-Director of the CCR Liver Cancer Program, found a strong link between the heterogeneity of tumors and patients’ responses to treatment. “Patients with short survival times tend to have more heterogenous tumors than those who have a more simplified tumor composition,” he explains.

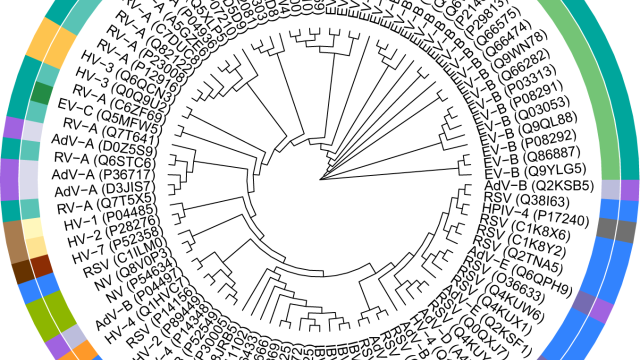

In this most recent study, Wang and his colleagues analyzed tumor samples from patients with HCC or iCCA. Importantly, some biopsies were taken both before and after patients were treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Wang’s colleague, Lichan Ma, Ph.D., a visiting postdoctoral fellow and bioinformatician, conducted a sophisticated, single-cell analysis to gain a detailed understanding of each tumor cell’s full protein profile. This provided an extremely thorough look at how cancer cells evolved over time, including after treatment.

The results show that a protein called osteopontin is consistently associated with higher tumor heterogeneity. This was true in both HCC and iCCA, even though these are two clinically distinct tumor types.

“In patients who are not responsive to treatment, this protein is elevated,” Wang says. “So functionally, this protein may be acting as the driver to make the tumor cells more likely to escape from treatment.”

These findings could lead to more effective treatment for people who do not respond to checkpoint inhibitors alone. “If we have a therapy that blocks osteopontin, in combination with a checkpoint inhibitor, presumably we can increase the treatment efficacy,” he says.

Wang is excited about this line of research, and while he will continue to study tumor evolution in liver cancer, he is also planning on collaborating with other CCR departments to apply this research to colon cancer that has metastasized to the liver.