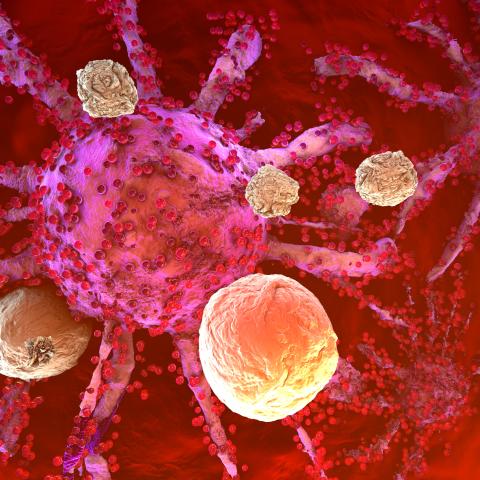

Immune cells (yellow) attacking a cancer cell (pink). Image credit: iStock

Scientists led by Steven A. Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., Chief of the Surgery Branch, have found antitumor T cells in the blood of patients with metastatic solid cancers. The cells are sparse, but with a newly identified signature, they can be picked out of the crowd. The discovery, reported November 23, 2023, in Cancer Cell, gives researchers a noninvasive method of obtaining tumor-targeting immune cells for the development of personalized cancer immunotherapies.

Cell-based cancer immunotherapies, pioneered in Rosenberg’s lab, use a patient’s own immune cells to attack their cancer. The approach has so far been most successful in treating melanoma, but Rosenberg’s team has shown that it can also shrink other solid tumors, including colon, liver and breast cancers. To target solid tumors, these therapies must be highly customized and designed to recognize mutations that are specific to an individual’s cancer.

To determine which cancer mutations are capable of triggering an immune response, Rosenberg and his team have looked to naturally occurring immune cells that recognize each patient’s tumor. Such cells can be found inside tumors, but the identification of antitumor T cells in the blood means they can now be obtained without surgery.

To find out whether tumor-targeting T cells circulate in the blood, the research team first isolated tumor-targeting T cells from the tumors of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Then they analyzed blood samples from the same patients, searching for T cells that shared the receptors the T cells inside the tumor had used to recognize their targets. Stadtman Investigator Sri Krishna, Ph.D., who carried out the study with Rami Yossef, Ph.D., a former scientist in Rosenberg’s lab, explains that the genetic sequences that encode T cell receptors are like natural barcodes, identifying immune cells that target the same mutated protein in the patient’s tumor.

Tumor-targeting T cells were found to be far rarer in patients’ blood than they are inside tumors, but they were present in each blood sample that the researchers examined. Once they had collected antitumor cells from the blood of several patients, Yossef and Krishna profiled the gene activity in each cell, looking for shared patterns. By doing so, they were able to identify a unique molecular signature for antitumor T cells in the blood. That signature successfully identified antitumor T cells in six of eight blood samples from patients with metastatic cancers, including colorectal cancer, breast cancer and melanoma.

The team also found evidence that blood-derived antitumor T cells are less exhausted than antitumor T cells inside tumors. They say it may be possible to use tumor-targeting T cells from the blood therapeutically by amplifying them in a lab and then returning them to patients. Researchers can also learn from the cells how to reprogram healthy T cells that don’t recognize tumors to make them therapeutic, as they have done with antitumor T cells isolated from tumors. “Utilizing these results, we can identify T-cell receptors that can recognize antigens on common cancers and put them into a patient's T cells for use in therapy,” Rosenberg explains.