CAR T-cell therapy

Image courtesy of NCI Visuals Online

A new immunotherapy for lymphoma has been found to cause lower levels of neurologic toxicity than other T-cell therapies for lymphoma. The findings, reported January 20, 2020, in Nature Medicine, come from the first clinical test of a CAR T-cell therapy using a new anti-cancer T-cell receptor developed in CCR. The receptor targets the CD19 marker on the surface of cancerous B cells. More than half of the patients in this phase I trial experienced complete remissions after receiving the treatment.

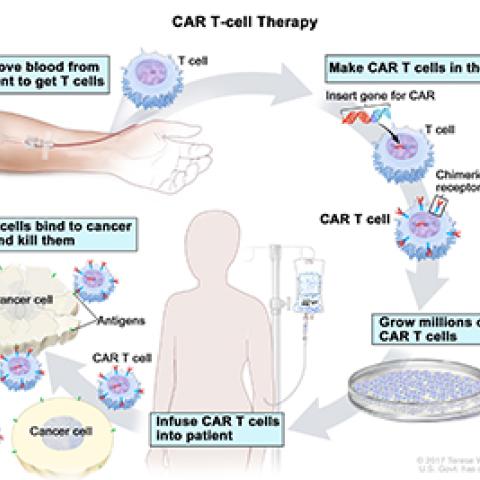

CAR T-cell therapies are cancer treatments in which T cells from a patient’s blood are genetically manipulated so that they produce a synthetic receptor that improves their ability to recognize and destroy cancer cells. That receptor is known as a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR.

Both FDA-approved CAR T-cell therapies for B-cell lymphoma use CARs that target CD19, a surface protein that cancerous B cells often express. Some patients experience complete remission of their cancer following this treatment. However, the treatment’s side effects can be severe. Many of the most significant problems are neurological, including speech problems, memory loss, tremors and seizures. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a potentially life-threatening inflammatory response, is less common but also a concern. These effects are thought to be triggered by CAR T cells’ release of substances called cytokines.

Development and testing of the new, less toxic therapy was led by James N. Kochenderfer, M.D., Investigator in the Surgery Branch. Like axicabatagene, an FDA-approved anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy for lymphoma, the new CAR targets CD19. In this case, however, Kochenderfer’s team modified the composition of the receptor, replacing two segments known as the hinge and transmembrane domains. In preclinical tests, the team determined that T cells that express this CAR, named Hu19-CD828Z, release lower levels of cytokines than T cells with different anti-CD19 CARs.

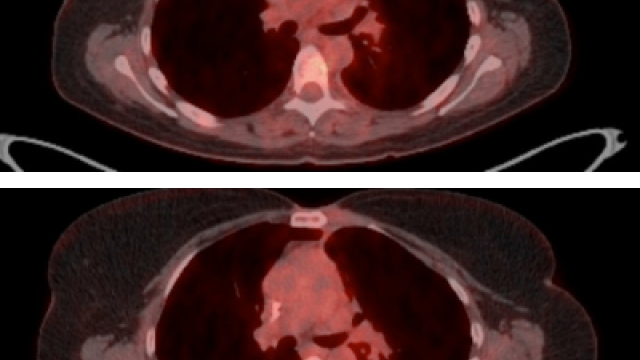

Now, the team has evidence of the dramatic effects CAR design can have on clinical outcomes, Kochenderfer says. Of the 20 patients with lymphoma who received the new treatment, only one experienced severe neurologic toxicity. There were no cases of CRS. In contrast, when the anti-CD19 CAR used in axicabtagene was tested in an NCI trial between 2013 and 2015, 50 percent of participants experienced severe neurologic toxicity. With the new Hu19-CD828Z CAR, only five percent of patients experienced severe neurologic toxicity. The new hinge and transmembrane domains do not appear to impair the CAR’s effectiveness. In both clinical trials, 55 percent of patients experienced complete remission of their lymphomas.

“Neurologic toxicity is a big problem with these CARs. I think we’ve really improved on that,” says Kochenderfer. “And our evidence so far is that the new CAR seems to be basically as effective as the more toxic CARs.”

Now that the team has established the safety of the new CAR, it is being incorporated into a potential next-generation CAR T-cell immunotherapy for patients with lymphoma, which Kochenderfer and colleagues have begun evaluating in a phase I clinical trial at the NIH Clinical Center. In that trial, patients’ T cells will be genetically modified to introduce two CARs—the new anti-CD19 CAR as well as a CAR targeting CD20, another protein on the surface of cancerous B cells. Because lymphoma cells can stop producing CD19, some patients become unresponsive to anti-CD19 immunotherapy and relapse. By programming patients’ cells to seek out both markers, researchers hope to generate more long-lasting responses to the treatment.