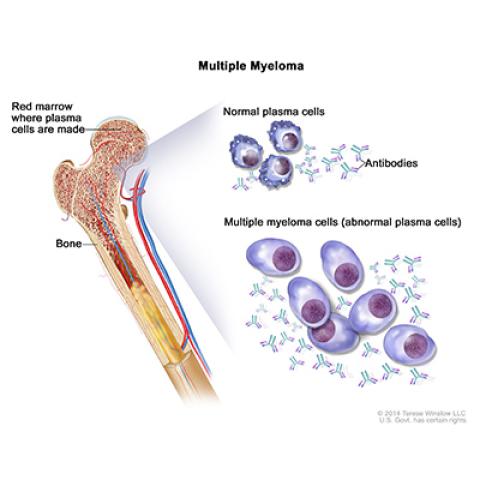

Multiple myeloma; drawing shows normal plasma cells, multiple myeloma cells (abnormal plasma cells), and antibodies. Also shown is red marrow inside bone, where plasma cells are made.

Photo credit: NCI Visuals Online

A phase I clinical trial of 33 patients infused with a CAR T-cell therapy using T cells genetically engineered to express an anti-B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) CAR showed that 85 percent of patients had the burden of their advanced multiple myeloma cut by half or more.

Additionally, 45 percent of the patients had a complete response, or no sign of disease, nearly a year after receiving the experimental therapy known as bb2121. The research, conducted by James Kochenderfer, M.D., Investigator, Experimental Transplantation and Immunology Branch, CCR, and colleagues was reported May 2, 2019, in the New England Journal of Medicine.

At the beginning of the CAR T-cell treatment process, a person’s blood cells were collected, and their T cells were genetically engineered in the lab to express a protein called a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR. The receptor targets a marker on the surface of multiple myeloma cells called BCMA. After the T cells have grown exponentially in the lab, they are re-infused into the patient and continue to multiply so they can mount a strong attack against the cancer.

“CAR T-cell therapy holds great promise to improve the treatment of multiple myeloma, and we have been actively conducting laboratory research and clinical trials at NIH using this approach,” says Dr. Kochenderfer. “We are currently conducting two CAR T-cell clinical trials for multiple myeloma at the NCI.”

Multiple myeloma is a type of cancer where white blood cells multiply uncontrollably in the bone marrow. Even with treatment, only about half of patients with multiple myeloma, which is usually diagnosed at a late stage, live for five years after diagnosis. Just over 30,000 cases of multiple myeloma were diagnosed in the U.S. in 2018.

The patients in this trial faced a poor prognosis. Despite numerous prior treatments, including many different types of chemotherapy and in most cases, stem-cell therapy, the patients’ disease became resistant to treatment. CAR T-cell therapy offers a new approach that may offer multiple myeloma patients another chance to benefit from treatment.

The trial was conducted in two parts, the first being a dose-escalation phase where patients got increasing amounts of bb2121 until a maximum tolerated dose was reached. In the next part of the trial, called a dose-expansion phase, patients were evaluated for safety, tolerability and activity of the therapy at a pre-specified dose of CAR T cells.

Notably, a response to the treatment occurred within just a few weeks for some patients, with the median response time being one month. There were, however, some concerning side effects, primarily related to blood, with neutropenia, leukopenia, anemia and thrombocytopenia being the most common. The researchers will continue to monitor patients to understand why these side effects occurred and how best to ameliorate them.

Dr. Kochenderfer notes that a phase II trial, called KarMMA (sponsored by Celgene, as was this trial), has already completed patient accrual in the U.S. and Europe.