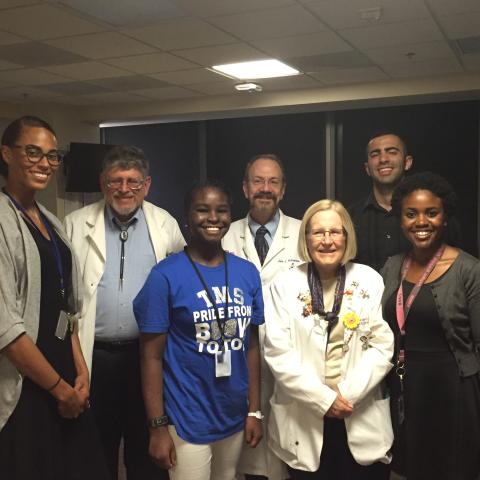

An 11-year-old XP patient (blue shirt, third from the left) at her fourth NIH visit for treatment in 2016. The patient and her family began coming to the NIH following her diagnosis at age four. From left to right: Raina Bembry (Howard University medical student), Kenneth Kraemer, M.D., XP patient, John DiGiovanna., M.D., (deceased), Deborah Tamura, R.N., Paul Hanona (Michigan State University medical student), Jennifer Pugh (post-bac student).

For over fifty years, Kenneth H. Kraemer, M.D., has investigated the molecular underpinnings, signs and symptoms of xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) and trichothiodystrophy (TTD). XP is a rare, recessive inherited disease with defective DNA repair that renders patients extremely vulnerable to ultraviolet (UV) damage from sunlight, resulting in cancers of the skin and eyes at an early age. TTD is a developmental disorder with defective DNA repair without increased cancer risk. XP and TTD can stem from different mutations in the same gene.

XP affects about one in a million people in the United States and Europe and 45 in a million people in Japan. People with XP are susceptible to severe sunburns after only minutes of sun exposure and are at a more than two-thousand-fold increased risk of developing skin and eye cancers. They are also at an increased risk of neurological degeneration, brain cancer and premature death.

XP was first described by dermatologist Moritz Kaposi in 1874 and reported to be caused by defective DNA repair by James E. Cleaver in 1968. That same year, Cleaver presented his findings on XP at the NIH, inspiring Jay Robbins, M.D., then Senior Investigator in the NCI Dermatology Branch, to begin clinical and DNA repair laboratory studies of XP patients.

Kraemer began working with XP patients at the NIH under Robbins in 1971, after receiving his medical degree from Tufts Medical School and training in internal medicine at Harlem Hospital. In 1974, Kraemer, Robbins and their expanding circle of colleagues published a landmark study on the first 15 XP patients studied at the NIH.

After departing for residency training in dermatology at the University of Miami from 1974 to 1976, Kraemer rejoined the NCI’s Laboratory of Molecular Carcinogenesis as a Senior Investigator and began to develop a functional assay to measure the extent of defective DNA repair in XP cells, which he detailed in 1985. Two years later, he and his colleagues conducted an extensive XP literature review, finding and analyzing records in the NIH Library and National Library of Medicine of 830 individual XP patients in reports published from 1874 to 1982.

They then published the first quantitative documentation of the increased skin cancer risk among XP patients, finding the median age of first non-melanoma skin cancer incidence for XP patients was 8 years old, more than 50 years younger than in people without XP. In 2011, Kraemer and his colleagues published a study of 106 XP patients examined at NIH over four decades indicating a more than two-thousand-fold increased risk in skin cancer in patients under 20 years of age.

Over his many decades at NCI, Kraemer has cared for and studied more than 700 XP and TTD patients. He assembled a world-class multidisciplinary research team along the way that featured the late dermatologist John DiGiovanna, M.D., and is currently bolstered by genetics-trained research nurse Debby Tamura, M.S., R.N.

His team also includes laboratory-based basic researchers led by staff scientist Sikandar Khan, Ph.D., and a multi-institute clinical team of ophthalmologists, neuro-radiologists, audiologists, neurologists, physiatrists, clinical photographers, psychologists, a gynecologist and a gastroenterologist. This cross-disciplinary mindset was demanded by diseases of DNA repair. In addition to treating XP patients for their acute symptoms and empowering them to prevent and manage their disease, the team has shaped the understanding of XP as a disease of premature aging.

In the Q&A that follows, Kraemer and Tamura discussed the work they have performed over the years that continues today:

What have been some of the most rewarding aspects of your career?

KK: The opportunities to see the patients and the laboratory work here at the NIH are just unrivaled. We have an incredible opportunity to bring the patients here, study them and get them the treatment they need.

DT: One of the wonderful things about being at the NIH is if somebody can get to the United States, we can then bring them here at no charge. We’ve seen patients from all over the world, including Saudi Arabia, Tanzania, Sudan and Australia. Once they’re here, we are able to do all kinds of lab work, X-rays, MRIs, CTS, hearing tests and an incredibly detailed ophthalmology exam. This has been extremely helpful in helping us to better understand and treat these conditions. Bringing these patients here also allows them to meet some other people who share the same rare disease: several of our XP patients’ families formed support groups after attending the NIH clinic.

One of the many things we do is identify the cancerous lesions caused by XP. We teach people how to protect themselves, which involves completely avoiding the sun, and how to manage their condition, which includes sunscreens and vitamin D supplementation. Today, we have people in our study who have lived to become grandparents.

KK: We did figure out a way to prevent people with XP from getting their skin cancers, just by taking oral isotretinoin (Accutane), the same medication that’s used for acne treatment, although it has many side effects.

We started out just studying the skin and cancer, and it actually moved us into a different realm, where we began to look at XP as a disease of premature aging, which can include premature menopause.

How has the mentoring you’ve been able to do shaped the future of the field?

KK: Many students have come through the laboratory in a number of different programs and at varying levels. Some are post-bacs about to go into medical school and some post-docs have just wrapped up medical or graduate school. Researchers who have trained with us are now running their own labs or clinics investigating XP across the United States, and in Germany and Japan, too. There was a group in London who got interested in XP and came to us, specifically to Debby, and said “we want to set up a clinic like yours in England,” and they did in 2010. Their clinic has since published detailed research about their XP patients.

Our clinical studies of XP patients at NIH, documentation of their different DNA repair defects and establishment of dozens of cell lines for use by researchers worldwide, provided a strong foundation for many researchers to build upon over the decades. It will be exciting to see the insights that those labs and others continue to gain in the years to come.

What frontiers of XP research are you most excited about?

KK: One percent of the Japanese population carries one copy of an XP founder mutation that confers a two to three times greater risk of skin cancer. Many more people have single copies of XP mutations than people with two copies of the mutation who manifest the disease. However, if you do the genetic calculations based on what we have found in the Human Genome database, there should be about 8,000 patients with two copies of the mutation in the United States rather than the 300 patients currently identified. So, we’re moving from a very rare disease to something that might be more common than we thought. The next frontier is to try to discover why these people have XP mutations with no symptoms or signs. It’ll be exciting to see that unfold.

Dr. Kenneth Kraemer and Debby Tamura will both be retiring from CCR on December 31, 2023.