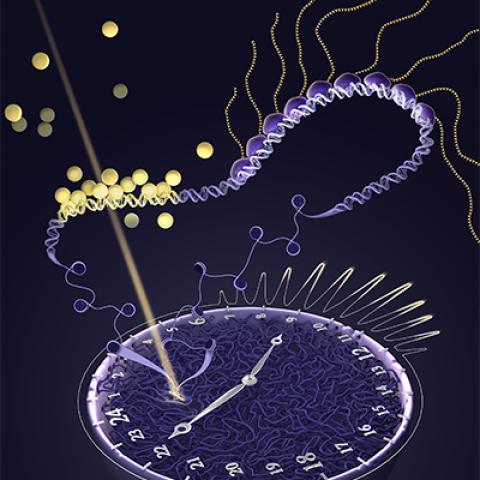

This cross-section of a cell nucleus shows glucocorticoid receptors (large yellow spheres) binding to DNA, trailed by strings of special molecules (small yellow spheres) that transcribe the DNA to RNA.

Image Credit:Veronica Falconieri Hays, Falconieri Visuals

Harnessing a cutting-edge imaging technique, CCR investigators have discovered that a pulsing pattern of hormone release regulates the pattern of transcriptional bursting in cells. They observed this at a gene-specific level in real time, a groundbreaking achievement. Transcription, which occurs in short bursts, is the process in which genetic information encoded by DNA is written into another type of molecule called RNA. The genetic information in RNA is later used to build proteins in a separate process. The findings appeared in print in Molecular Cell on September 19, 2019.

A team led by Gordon L. Hager, Ph.D., Chief of the Laboratory of Receptor Biology and Gene Expression, focused on glucocorticoids, a class of hormones that play crucial roles in regulating immunity, metabolism and many other physiological processes. Glucocorticoids bind to glucocorticoid receptors, found on nearly all cells in the body, triggering the transcription of various genes. The adrenal glands located atop the kidneys release pulses of glucocorticoids about once every hour.

To investigate the relationship between patterns of glucocorticoid release and transcriptional bursting, Hager and colleagues inserted a mammary mouse tumor virus (MMTV) gene into the collection of genes that comprise mouse mammary carcinoma cells. MMTV is glucocorticoid-regulated, meaning that whenever glucocorticoids bind to their receptors, the gene is transcribed into RNA. The researchers used a fluorescent-labeled protein that would attach to the newly transcribed RNA to observe RNA synthesis in real time.

The scientists treated the cells with two types of glucocorticoids. Using an advanced high-throughput microscopic imaging technique to observe transcription at individual MMTV genes in live cells, they compared the transcription patterns resulting from constant versus pulsed glucocorticoid stimulation. Constant stimulation resulted in random bursts of transcription, while pulsed stimulation resulted in bursts of transcription that lasted only as long as the pulse.

Earlier technologies had allowed researchers to average transcription factor dwell times over the entire genome and infer what happened at individual genes. However, using a novel imaging technique called 3D orbital tracking (3DOT) Hager’s team corelated bursting at a specific gene, as well as the proteins involved in transcription arriving at the gene. “This has been a holy grail in the field for many years now,” Hager says.

The researchers also noticed that genes located near each other tended to burst in a coordinated fashion; this makes sense because neighboring genes share a similar microenvironment. But surprisingly, genes on opposite sides of the cell nucleus, which houses the genome, also co-burst. Hager’s team thinks this could reflect mechanotransduction as interfering with the integrity of the cytoskeleton, which inhibited the force generation in the cells, selectively inhibited the co-bursting of these distal genes. Mechanotransduction has been observed in tumor cells, whose greater stiffness compared to healthy cells can affect the tumor cells’ gene expression.

Since glucocorticoids regulate a plethora of physiological processes, the new findings could improve our understanding of cancer and other diseases. They could also have implications for steroid drugs, including synthetic corticoids, which are used in treating arthritis, lupus and cancer, for instance, but have serious side effects. “If you’re going to figure out how to make numerous better drugs, you’re going to figure out how these glucocorticoids work,” Hager says. Overall, his team’s study could have research and clinical relevance for a broad array of conditions.