Dr. Troy McEachron

Troy A. McEachron, Ph.D., joined the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) this year as an Investigator in the Pediatric Oncology Branch (POB). He studies osteosarcoma, the most common bone tumor arising in pediatric and young adult patients. For this Sarcoma Awareness Month Q&A, he discusses the differences between osteosarcoma microenvironments in the primary and metastatic sites as well as his personal goal for increasing the participation of underrepresented populations in clinical research.

What sparked your interest in cancer research?

My first laboratory research experience was in the summer between my sophomore and junior year of college in a developmental immunology lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. I found it incredibly fascinating, and I just stuck with it. There is never a day that goes by that I’m not completely humbled and left in a state of awe by the data. But it’s also a fantastic motivation to try and know more.

As a new CCR scientist, what aspects of working here excite you the most?

I’m currently in the process of building my laboratory team, and the larger POB team has been very supportive and collaborative. I’m tremendously excited about the bench-to-bedside-and-back research opportunities and the chance to interact closely on a daily basis with my clinical colleagues to make sure that the work we’re doing will serve the patients here. Being able to engage in this manner as a Ph.D. scientist in the field of pediatric cancer research, while still pursuing quality hypothesis-driven research, is very unique to CCR and is rare in most extramural academic environments. I don’t think there’s any other place I’d rather be working than CCR; this is definitely a dream job scenario.

What are your research interests, and what research question or challenge are you currently pursuing?

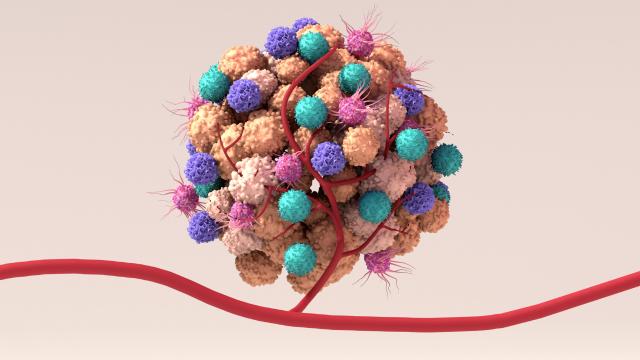

My main interests are pediatric sarcomas, which are tumors of the connective tissues, such as muscle, bone and cartilage. I really want to understand the tissue-specific microenvironment of these malignancies – how do tumor cells and non-tumor cells interact with each other in different tissues in the body? This is very important for being able to identify effective therapies.

The five-year survival for patients with localized osteosarcoma is about 70 percent, but for patients who have metastatic disease that has spread to other parts of the body, the survival percentage drops to about 30 percent. Patients with advanced disease don’t usually respond to immune checkpoint inhibitors, a form of therapy that has proven efficacious in various other cancers. My question is why, and does this hold true for other immunotherapeutics?

In previous work, my colleagues and I looked at primary osteosarcomas that originated in bone, and then we looked at metastatic osteosarcomas that traveled to the lungs of patients. We found that immune cells were sparsely scattered throughout the primary tumors in bone, but immune cells were found only along the periphery of the metastatic lung tumors. I’m interested in understanding how we can increase the infiltration of these immune cells inside these metastatic tumors. If we can do that, then this might increase the efficacy of numerous immunotherapeutic approaches that are currently available as well as those in development.

What one area of your research is most urgently in need of attention?

Increasing participation of underrepresented minorities in clinical trials is really important. As a black male scientist, that’s something I take very seriously.

When I look at the genomic profiling studies and the landscape of pediatric cancer research, it is not reflective of the demographics by any means. We know there are certain aspects of cancer biology where your genetic ancestry plays a role, but people of color tend to be underrepresented in clinical studies. In order to really answer questions about cancer for all patients, we need to diversify the population of people participating in trials.

This is something very near and dear to my heart. Along with running a laboratory, I’d like to be involved in increasing participation in clinical trials, whether it’s through community initiatives or bringing awareness through more formal channels.

Tell us about a patient who stands out to you.

I remember this vividly. When I was a postdoctoral fellow at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, I had the opportunity to interact with patients and their families through my wife, who is a pediatric hematology oncology nurse. One day, as I was walking to the hospital parking lot, I ran into a patient and her mom, both of whom I got to know over time. The mother asked me, “Have you done anything today to help my child?”

That was an incredibly sobering moment. I remember turning around and going back up to the lab and contemplating what the heck just happened. I realized that my research is a lot bigger than just my career. I am here to help people. So that experience was formative, and I’ll never ever forget that.

What advice do you have for future generations of cancer researchers?

You have to love what you do because science is not easy; it’s incredibly tough. You have to enjoy the intellectual pursuit. Ask a lot of questions, and don’t let people dictate what that looks like for you because there’s no one way to ask a question. When you go through training, the goal isn’t to be a miniature clone of your mentor; the goal is to be able to amass a skillset and thought process that will allow you to tackle tough questions. I think that’s really important for anyone pursuing science.