The Translational Research Program is dedicated to developing clinical trials for people living with a brain and spine tumor—which requires research in a laboratory and patient observations in the clinic.

By Neuro-Oncology Branch Staff

September 28, 2021

Developing clinical trials for people living with brain and spine tumors is no easy feat. It takes a considerable amount of research in a laboratory and patient observations in the clinic to develop new ways to treat the disease and improve outcomes. The Translational Research Program at the NCI Center for Cancer Research's Neuro-Oncology Branch (NOB) is dedicated to doing just that.

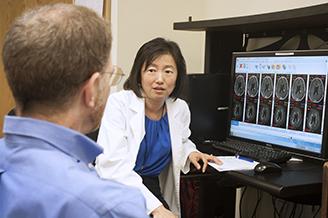

The Translational Research Program is led by Lasker Clinical Research Scholar and Investigator Jing Wu, M.D., Ph.D. Dr. Wu received her medical degree from Capital Medical University in Beijing, China and her Ph.D. in neuroscience from the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. She then completed a neurology residency at University of Texas at Houston and a subspecialty fellowship in neuro-oncology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. With training in both basic science research and clinical research, Dr. Wu realized that researchers can make a great difference in the field. This motivated her to pursue translational research, combining both clinical and laboratory research.

Using Clinic Observations to Improve Research and Care

Translational research is the process of taking scientific discoveries from the laboratory to the clinic, so researchers can observe how patients respond to a new treatment developed in preclinical models. Once clinical observations are made, these results are taken back to the laboratory to inform research. This iterative process allows investigators to study a focused clinical question in the laboratory, where they can safely test hypotheses before giving the treatment to people.

Dr. Wu’s approach to translational research starts with patient care. This helps her pick a research topic, and then based on her observations from her clinical practice she picks a focused clinical question to study. “I will take that question to the laboratory and investigate it in preclinical models. This allows us to better understand what we saw in the clinic by conducting a study in the laboratory,” she says. Once she has a rigorously-tested laboratory finding, Dr. Wu and her team test their hypothesis through a clinical trial with brain and spine tumor patients and continue to make further observations.

Translational research is a “back and forth process, not a one-way trip,” Dr. Wu explains. “You have to go back and forth frequently to better understand the disease. This process helps us understand why some patients might respond better to a specific treatment than others, informing precision medicine approaches.”

Translational Research Program

The goal of Dr. Wu’s Translational Research Program is to identify and address important clinical problems and barriers to progress in neuro-oncology. Her aim is to ultimately improve scientific knowledge and clinical practice.

Dr. Wu finds that translational research is especially important because brain and spine tumors are quite unique. “Understanding both the clinical and laboratory parts of neuro-oncology helps me to develop focused research projects that lead to clinically relevant results and guide clinical practice,” Dr. Wu says.

The Translational Research Program works closely with the Radiation Oncology Branch and Molecular Imaging Branch at the NCI Center for Cancer Research, as well as the National Institute of Mental Health at NIH. Dr. Wu’s laboratory uses metabolic imaging to monitor patients with brain and spine tumors, in order to capture when the disease progresses. More specifically, Dr. Wu’s laboratory investigates why and how tumors become malignant (cancerous) in a subset of patients with IDH-mutated gliomas. Because this transformation is a process that cannot be mimicked or created in a laboratory setting, Dr. Wu’s team monitors patients closely in the clinic with metabolic imaging. Their goal is to capture when a tumor might be transforming into a higher grade. This clinical imaging technology allows Dr. Wu to capture a window of opportunity to obtain tumor tissue and further investigate this in her lab. “This clinical trial program creates the opportunity to understand what causes tumor transformations, so they can be detected early and we can intervene to turn the slow progression into a chronic state,” Dr. Wu explains.

One of Dr. Wu's recent accomplishments was a successful phase 1 trial. It tested the novel agent zotiraciclib in combination with temozolomide to treat recurrent anaplastic astrocytoma and glioblastoma.

Through a very thorough preclinical study, Dr. Wu’s team was able to introduce this new drug—which had never been tested before in patients with brain tumors. Gliomas comprise about 30 percent of all brain and central nervous system tumors and 80 percent of all cancerous brain tumors. Thanks to Dr. Wu's work, zotiraciclib was recently given orphan drug designation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

During this early phase clinical trial, a subset of patients had a better response to the experimental therapy. This led to ongoing research to confirm the findings in preclinical models and explain the underlying mechanisms in the laboratory. Dr. Wu’s team is actively working with NOB Chief Mark Gilbert, M.D., to open the phase 2 study of zotiraciclib plus temozolomide versus temozolomide alone in recurrent high grade glioma patients.

Dr. Wu credits her success to strong mentorship and collaboration throughout her career. With the help of her hard working, supportive and passionate team in the clinic and laboratory, Dr. Wu feels confident she will make a difference in the field. “At the end of the day, we only have one goal: for our brain tumor patients to live longer with a good quality of life,” she says.