The Translational Immunology Research Program is studying the unique nature of the immune response in the brain to improve patient outcomes.

By Neuro-Oncology Branch Staff

June 28, 2022

Immunotherapy is an important area of research in neuro-oncology, because it has the potential to be an effective treatment for brain tumors. Research shows it can improve outcomes for many cancers, but more research is needed on the unique nature of the immune response in the brain—and why only certain brain tumor patients respond to treatment.

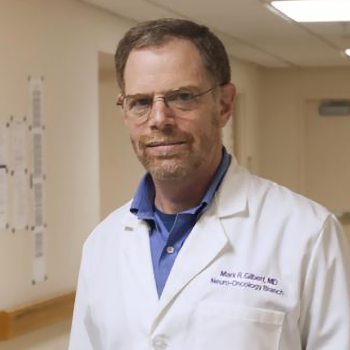

That’s why Mark Gilbert, M.D., chief and senior investigator at the NCI Center for Cancer Research's Neuro-Oncology Branch (NOB), is leading research in immunotherapy and precision medicine for brain tumors as head of the Translational Immunology Research Program.

“The research goals of the Translational Immunology Research Program are to create clinical studies that include a strong laboratory component to better understand why some patients respond to treatment and others do not,” Dr. Gilbert says. “We are also looking at the effects of other treatments on the immune response and finding ways to either avoid these treatments or reverse their negative effects.”

Dr. Gilbert received his medical degree from Johns Hopkins University and completed residencies in internal medicine, neurology, and a neuro-oncology fellowship. Over the course of his 35-year career, Dr. Gilbert has been an integral part of various national and international clinical trial initiatives. His robust research program includes a multidisciplinary team of clinicians and scientists who aim to improve treatments and patient outcomes.

The Basics of Translational Immunology Research

Translational immunology studies ways to improve immunotherapy in clinical trials. Immunotherapy is a type of treatment that uses substances to stimulate or suppress the immune system to help the body fight cancer.

“When it's working properly, the immune system will recognize a virus or bacterium and then fight it. But when the immune system encounters abnormal cancer cells, there is virtually no immune response without some help,” Dr. Gilbert says. “This is because the cancer has developed a way to bring in immune cells that are designed to suppress immune function.”

Dr. Gilbert is studying ways to reduce the amount of immunosuppression that the body responds to, so that it is not fighting against efforts to generate an immune response. His research team uses a "bench-to-bedside and back-to-bench" approach, which uses findings from laboratory experiments to develop clinical trials. Then, clinical trial observations from the trial go back to the laboratory. This type of collaborative approach helps researchers and clinicians work together to improve outcomes for patients, which has been successful for other cancers.

For example, a type of immunotherapy drug called immune checkpoint inhibitors has changed the cure rate for certain cancers from zero to over 40 percent. Unfortunately, the cure rate of glioblastoma, the most common type of brain tumor, is zero—and the five-year survival rate ranges from five to 22 percent depending on the patient’s age. Dr. Gilbert and his team in the Translational Immunology Research Program are hopeful that their immunotherapy research will lead to similar advances in patients with brain tumors.

Their research is focused on developing combination therapies that can send more immune cells to the tumor site. By understanding the characteristics of brain tumor patients, clinicians can improve patient selection for immunotherapy clinical trials and maximize treatment benefits for the patients participating.

A Discovery Leads to a Clinical Trial

Almost every patient with a brain tumor is treated with steroids, but it was not well understood how steroids affect a patient’s response to immunotherapy. Dr. Gilbert’s lab did some of the early work investigating what happens to healthy immune cells in people without a brain tumor after steroid treatment. The researchers discovered that steroids nearly completely inhibit the immune cell’s ability to respond to immunotherapy.

“This was an important discovery, because nearly every patient with a cancerous brain tumor is prescribed steroids. In some of the pivotal clinical trials, many patients were on steroids when they received immunotherapy,” Dr. Gilbert says. “Now that we know steroids prevent a response to immunotherapy, those patients—even if they could have responded—would not have responded because of the steroid medication.”

This discovery led Dr. Gilbert and his team to develop a clinical trial, which monitors the immune response in people with glioblastomas who are not on steroids. The trial tests if immune checkpoint inhibitors given with standard treatment result in an immune response. “We are monitoring a patient’s immune response in their blood to see if those who have an immune response also have better outcomes and survive longer than those who do not get an immune response,” Dr. Gilbert says. This trial will also evaluate a test that may help determine who is likely to get that response.

Dr. Gilbert and his team are hopeful that this study may be the first to demonstrate that an immune response could improve survival rates, suggesting that the immunotherapy is beneficial for people with glioblastomas.

Dr. Gilbert explains that if a patient's immune cells are able to reach the brain tumor, they will likely affect the brain cancer and improve outcomes. The next step is to figure out who gets the immune response by analyzing the clinical trial data. Researchers will evaluate clinical characteristics such as age, gender, race, and genetics, comparing the responders and non-responders.

Determining which glioblastoma patients have an immune response will help Dr. Gilbert and his team develop a clinical trial to further study the effects of immunotherapy.

The Future of Translational Immunology Research

Dr. Gilbert and his team collaborate with other NOB research programs that are conducting complementary immunology studies. Dr. Gilbert is also studying the immune microenvironment in tumor samples from a clinical trial testing a vaccine, because a group of glioblastoma patients on the trial had unexpected long-term survival.

“This may give us insight into what the surrounding components of the tumor are, in a setting where there is a good immune response,” Dr. Gilbert says. “Given the complexity of cancers in the central nervous system, we need to carefully understand what is unique about those cancers. That way, when we use immunotherapy, we are doing whatever we can to enhance it and not inadvertently disable it.”

Dr. Gilbert hopes to give immunotherapy every chance to be successful in patients with brain tumors. “Hopefully, we can emulate our colleagues in other cancers who have had some amazing successes with immunotherapy—and provide our patients with the same improved outcomes.”