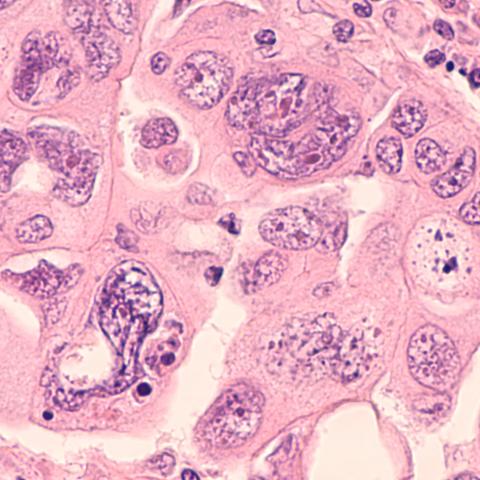

Ovarian cancer cells under a microscope. Image credit: iStock/rightdx

Drugs that inhibit the enzyme CHK1 may be beneficial for some patients whose ovarian cancer has become resistant to PARP inhibitors, a class of drugs used to prevent certain ovarian cancers from recurring after treatment. Researchers led by Jung-Min Lee, M.D., a Lasker Clinical Research Scholar in the Women's Malignancies Branch, have now identified two genes whose activity could help determine which patients are the best candidates for such drugs. Their work is reported June 21, 2023, in Science Translational Medicine.

PARP inhibitors, which kill cancer cells by interfering with their ability to repair damaged DNA, were first approved for the treatment of certain ovarian cancers in 2014. They are often effective for women whose ovarian cancer has mutations in the DNA repair genes BRCA1 or BRCA2, and are now commonly used to prevent recurrence in these patients. However, most patients eventually become resistant to PARP inhibitors, and their cancer often returns.

“This is a very important subgroup of patients with an unmet need,” says Lee, a physician-scientist who has been frustrated by the lack of options for treating this type of ovarian cancer once PARP inhibitors stop working.

Lee and her team, including Medical Research Scholars fellow Nitasha Gupta, M.D., research fellow Tzu-Ting Huang, Ph.D., and biologist Jayakumar Nair, Ph.D., launched a research effort dedicated to finding a treatment for this emerging group of patients. They began by working with the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) at NIH to test the effects of 2,450 different compounds on ovarian cancer cells that had mutations in BRCA genes and were resistant to PARP inhibitors. One of the best killers of those cells was prexasertib, an experimental cancer therapy that blocks DNA repair by inhibiting the CHK1 enzyme. Follow-up experiments revealed that the drug increases DNA damage in the PARP inhibitor-resistant cancer cells, which can lead to their death.

When Lee and her colleagues tested prexasertib in a clinical trial, only one of 17 patients with PARP inhibitor-resistant ovarian cancer had an objective response to the drug, meaning tumors shrunk by at least 30 percent. Four patients saw their tumors shrink or stabilize for at least six months, which Lee and her colleagues considered a durable clinical benefit.

Using tumor biopsies collected during the clinical trial, Lee and her team discovered that the cancer cells from women who benefited from the treatment had unusually high activity in two genes, Bloom syndrome RecQ helicase (BLM) and cyclin E1 (CCNE1). CCNE1 activity is associated with high levels of DNA damage response, and Lee’s group had previously linked it to a positive response to CHK1 inhibitors. In new laboratory experiments, they confirmed that PARP inhibitor-resistant, BRCA-mutated ovarian cancer cells are more sensitive to CHK1 inhibitors when BLM is overactive, too.

The new knowledge has been incorporated into the design of an ongoing clinical trial led by Lee, which is evaluating prexasertib in patients with ovarian, endometrial or bladder cancer. Participants will be tested for a molecular signature that may be associated with a positive response to CHK1 inhibitors. Patients with the signature, which comprises several molecular features of cancer cells related to DNA damage and repair, will receive prexasertib alone. Patients without the signature will receive prexasertib in combination with chemotherapy.