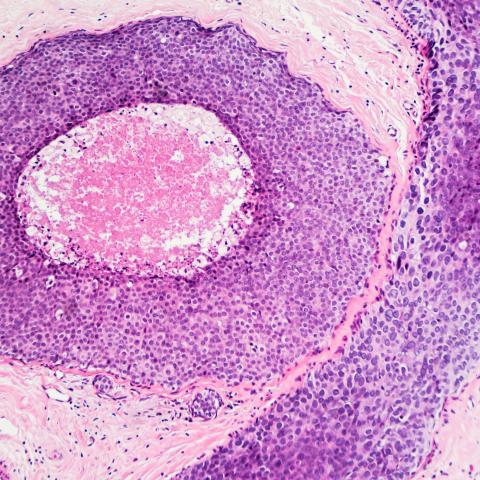

Breast cancer cells in situ. Image credit: iStock.

CCR scientists have compared genetic mutation patterns in breast cancer tumors from three groups of patients — African Americans, European Americans and Kenyans — and found differences between the three groups. The different tumor mutation profiles, reported November 7, 2023, in Cancer Research Communications, may reflect differences in the biological and environmental factors that promote breast cancer development in each group of patients.

The research, led by Stefan Ambs, Ph.D., M.P.H., Senior Investigator in the Laboratory of Human Carcinogenesis, and Francis Makokha, Ph.D., Head of the Human Health Research Programme at Mount Kenya University, is a step toward unraveling the biology of breast cancer across population groups, with a focus on women of African descent.

Greater breast cancer mortality among African American women is likely due to differences in healthcare access, but Ambs says this does not fully explain the disparity. African Americans disproportionately develop aggressive subtypes of breast cancer, and studies have found that these subtypes are common among patients in Africa as well. Researchers are working to understand how ancestry, socioeconomic and environmental factors and other conditions contribute to these disparities.

The team’s discovery that tumor mutation patterns show population-specific differences came from an analysis of breast cancer tumors from nearly 200 African American, European American, and Kenyan patients, as well as healthy tissue samples from the same individuals. The group-to-group differences most prominently affected genes in which mutations are uncommon. Certain mutations that occur infrequently were found at different levels in each of the three groups. Most notably, Ambs says, mutations in a gene called ARID1A were found at an increased frequency in tumors from Kenyan patients. This was of particular interest because patients whose tumors carry mutations in ARID1A may not respond to hormone therapies, the first-line treatment for many breast cancers. Ambs and his collaborators are now conducting further studies of a larger set of breast cancer tumors from Kenyan patients to assess the frequency of ARID1A mutations in that population.

The researchers also looked for correlations between patients’ disease and the environments in which they lived. For patients in the United States, who were recruited in Maryland, they considered each neighborhood’s deprivation index — a measure that integrates data about wealth, occupations and housing conditions. This data was not available for Kenyan patients. The analysis showed survival times were shorter for individuals living in neighborhoods with high deprivation scores. This was true regardless of patients’ personal income, education, self-reported race and disease stage. However, the team found no evidence that linked neighborhood deprivation to particular tumor mutation signatures.

Ambs says larger studies are needed to determine which tumor features might be shaped by neighborhood conditions. “We would say this is the pilot study,” he says. “It can be done, and in the future, this has to be done at a much larger scale.”