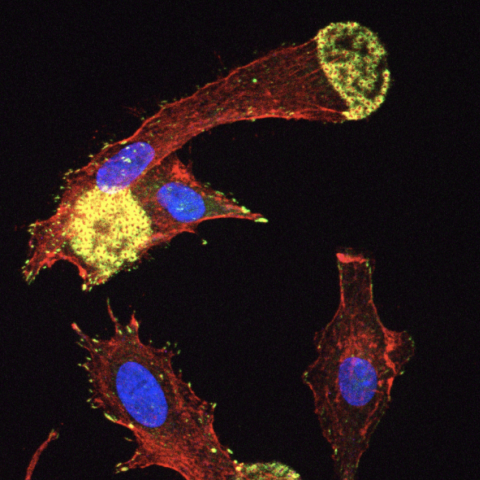

After gene therapy to restore the missing WAS gene in people with Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, dendritic cells are able to form podosomes (seen in the image), essential structures for cell movement and function. CREDIT: Roxane Labrosse, Julia Chu, et al.

A clinical trial showed that a gene therapy for Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) successfully improved the symptoms of five young boys affected by the disorder, with benefits sustained for years following therapy. The results are described in a study published October 12, 2023, in the journal Blood.

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS) is a rare genetic disorder whereby boys carry mutations in a gene called WAS, which produces an important protein for healthy blood cell functioning. As a result, people with WAS have low numbers of platelets (cells that usually promote clotting), thus they can experience serious bleeding with minimal trauma. Patients can also have eczema, increased risk of infection, autoimmunity, lymphoma and a reduced life expectancy. The only standard curative treatment for WAS is a blood stem cell transplantation that requires a suitably matched donor and has potentially life-threatening complications.

Sung-Yun Pai, M.D., Chief and Senior Investigator in the Immune Deficiency Cellular Therapy Program, sought to explore the use of gene therapy for treating WAS. Gene therapy involves using a virus as a vector, or carrier, to deliver the missing gene into the patient’s own cells, thereby allowing the patient to produce the missing protein.

In their clinical trial, Pai’s team removed blood stem cells from five boys with WAS, used a lentivirus as a carrier to deliver the missing gene into the cells, and then reinfused the genetically modified cells back into the study participants after chemotherapy to replace their remaining stem cells. Along with assessing the patients’ symptoms over time, the researchers analyzed how successfully the virus delivered new copies of the WAS gene into the blood stem cells.

The scientists confirmed that the genetically altered blood cells in all patients had gained at least one copy of the missing gene, and some patients’ cells had gained two or more copies. All five study participants were successfully reinfused with their genetically modified blood stem cells and, over the course of a median follow-up period of 7.6 years, showed improved immune function, disappearance of eczema, fewer infections and less bleeding. The results also showed that the number of genes successfully added to the blood stem cells correlated with patient outcomes. For example, patients with at least two copies of the gene in the blood stem cells had better platelet counts, improving to near-normal levels.

“I was just thrilled,” says Pai. “As we followed these patients over the years, it was very gratifying to see them get better. Two patients developed near normal platelet counts; it was great to see them be able to play, engage in contact sports — do things that other little boys do.”

Of note, two other patients had pre-existing autoimmune conditions, wherein the body attacks healthy cells, and they experienced a flare-up of autoimmune activity following the gene therapy treatment. While the flare-up ultimately resolved in these patients, the Pai lab is continuing to try to unravel the reason why this occurred and figure out how to prevent this from happening. Due to improved immune function, Pai believes these boys will be protected from developing lymphoma in the future.

Despite the small sample size, in keeping with the rarity of this disease, these highly positive results provide strong early evidence of the benefit of this gene therapy for WAS and add to the potential of this therapy as an alternative to standard allogeneic transplant.

These insights have prompted Pai and her team to investigate additional viral vectors that may be more effective at replacing the WAS protein. “We have collaborators who have developed such a vector,” she says. “We’re going to assist them in developing a clinical trial that we will ultimately host here at NIH.”