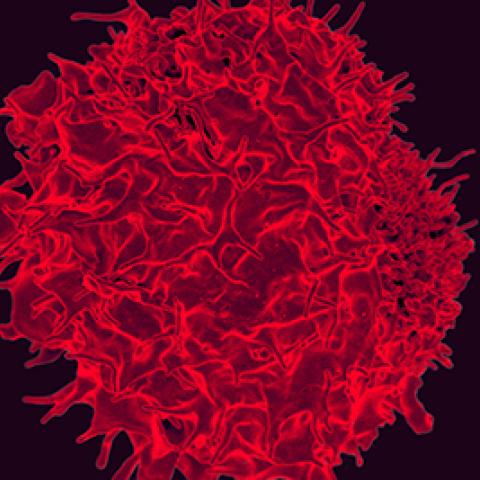

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a T lymphocyte.

Credit: NIAID, NIH

CCR scientists analyzed gastrointestinal tumors from 75 patients and found T cells responsive to tumor-specific antigens in 83 percent of those tumors. This finding suggests that many common gastrointestinal tumors may bear mutations capable of eliciting an immune response, suggesting that immunotherapy could be an effective way to treat these common cancers.

Immunotherapies, which empower the body’s own immune system to fight disease, are revolutionizing the treatment of certain cancers. But many common cancers, including colorectal cancer and other gastrointestinal cancers, have been less responsive to these innovative therapies. One concern has been that these cancers may lack the kinds of tumor-specific mutations that can alert the immune system of their presence and trigger an attack. This new study, published June 4, 2019, in Cancer Discovery, by Surgery Branch Chief Steven A. Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues, gives pause to that concern.

The researchers began their study by sequencing the protein-coding DNA in both normal and cancerous tissue from the 75 patients whose tumors had originated in the rectum, colon, bile duct, pancreas, stomach or esophagus, all parts of the gastrointestinal tract. By comparing the DNA sequences, they identified all of the mutations that distinguished each patient’s tumor from his or her healthy tissue. Individual tumors had between 22 and 928 such mutations.

The team also collected T cells from each tumor and grew them in the laboratory. Using a high-throughput screening method developed in Dr. Rosenberg’s laboratory, the researchers assessed whether these tumor-infiltrating T cells were able to recognize bits of protein encoded by the cancer-specific mutations present in the tumor from which the immune cells had been isolated. When such molecules trigger an immune response, they are known as antigens.

Fewer than two percent of the gene products that the team screened elicited a response among the cultured T cells, but the team found tumor-infiltrating T cells responsive to at least one cancer-specific antigen in 83 percent of the patient tumors in their study. More than half of the tumors contained T cells that recognized and responded to multiple antigens. Almost none of the immune-activating mutations were shared among patients. Instead, T cells recognized antigens that were unique to the patient’s tumor from which they had been isolated.

Rosenberg says the new findings, along with similar findings his team has made in breast and ovarian tumors, suggest that the majority of tumors are capable of triggering an immune response. “It is ironic that the very mutations that caused the cancer can be the targets of effective immunotherapy,” he says. “These data show that the majority of the common epithelial cancers are potentially susceptible to effective immunotherapy."