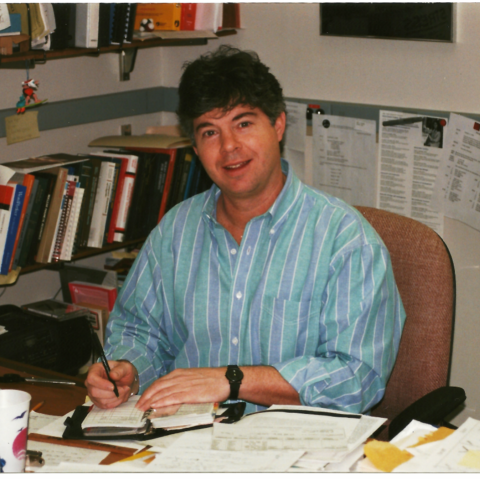

Dr. Byrd sitting in his office at NCI Frederick, circa 1993. Photo provided by Dr. Andy Byrd.

32 years ago, R. Andrew “Andy” Byrd, Ph.D., came to NCI Frederick to study the foundational biophysics of cancer. After an extensive career developing and utilizing nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy methods to determine protein structures and mechanistic insight, he has announced his retirement.

Byrd received his B.S. in chemistry from Furman University in 1973, followed by his Ph.D. in physical chemistry from the University of South Carolina in 1977. He then began his research career at the National Research Council in Ottawa, Ontario, before moving to Bethesda and joining the NIH. At the time, the Food and Drug Association (FDA) had a research building on the NIH campus where Byrd worked for almost a decade studying polysaccharide and oligodeoxyribonucleic acid structures. In 1992, he moved to NCI Frederick to head the Macromolecular NMR Section of the Macromolecular Structure Laboratory. He then established the Structural Biophysics Laboratory (SBL) and served as its Chief from 1999 to 2017. In 2020, this lab combined with another to form the Center for Structural Biology, where Byrd remains a Senior Investigator and head of the Macromolecular NMR section until his retirement.

At NCI, Byrd has developed NMR techniques to study the fundamental biophysical properties of proteins and understand their dynamics and mechanisms of action in the context of cancer-related systems. Early in his NCI career, he characterized the structures and interactions of components of the hepatocyte growth factor system, ultimately leading to the design of agonists and antagonists that could bind to its receptor and modulate activity. In recent years, Byrd has focused his efforts on studying dynamic protein-protein interactions in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, as well as the ADP-ribosylation factor (Arf) GTPase-activating protein (GAP) system, which has implications for membrane trafficking and cell migration.

Byrd’s lab is renowned for its work in structural biology and using NMR to elucidate complex biophysical processes. His fundamental research provides a foundation that sets others up for success in cancer research.

“You need to understand principles and foundational knowledge, and that’s what our group has always worked on. Then, through collaborations, it leads to biological understanding and possibly therapeutic interventions,” says Byrd.

In the Q&A that follows, Byrd reflects on the accomplishments in his career and the future of cancer research.

Which scientific achievements are you most proud of?

In research, I think I’m most proud of our work studying the hepatocyte growth factor system, the interplay between E2 and E3 enzymes in ubiquitination, and the Arf-GAP system. These topics are all very different and very challenging, yet this research has led to our great accomplishments and papers.

On the project development side, I was the founding lab chief of the SBL and held that position for 17 years, where we tried to build interdisciplinary approaches similar to what I did in my research, but with other principal investigators. Along the way, I helped revitalize chemistry research in CCR which led to the establishment of the Chemical Biology Lab and for a short time, the Molecular Discovery Program, which combined screening, chemistry and structural biology.

In the extramural community, I chaired a number of international conferences and served on the advisory board for the worldwide Protein Data Bank (PDB), which is the single international repository of structural data for proteins. It was very gratifying to get everybody together and create things on an international scale. It was that platform that led to the now-popular AlphaFold system that uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to predict 3D protein structures based on primary sequences. Those models were trained on the PDB, so being involved with that for 17 years was really quite a delight.

What do you see as the most exciting frontiers in cancer research?

As our knowledge and awareness of biology have become so much more sophisticated, it’s exciting to see researchers trying to look at larger, multi-component and in situ systems within the whole organism and modify their biology or the way they operate. New techniques are enabling such studies and support the philosophy of first understanding the fundamental mechanisms and then modulating them. Therapeutically, there are things like proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) that bring together multiple systems to modulate a biological pathway. That kind of specificity and selectivity in treatment is very exciting.

How did the intramural environment of CCR help your research?

It's been great. I came to the main campus of NIH in 1983 but actually worked at the FDA. They had a research building on the main campus and I was part of an intramural group applying fundamental principles of physics and chemistry to biology.

It has always been interesting to follow where the science goes, and that's a unique quality of the intramural program. Here, if you want to change paths because you have a new idea or a different direction, you can do that as long as you're doing good science. We have the flexibility to reach out to colleagues and combine knowledge. That flexibility and interdisciplinary support have been really fantastic.

Do you have any advice for future generations of cancer researchers at CCR?

Take advantage of the uniqueness of the place in terms of expanding your knowledge and reaching out to people who aren't doing what you're doing. Talk to everyone and keep a very open mind. You want to avoid getting trapped doing only what you’re good at and what you already know how to do. That will give you success for a short period of time, but in the long run, you need to be flexible, open-minded and follow new ideas.

What are you most looking forward to during your retirement?

In this business, you tend to do about 90% science and about 10% the rest of your life. I'm looking forward to rebalancing that. I'll remain at NIH as an emeritus and stay connected with the field, but I’m excited to do all the things I love to do outside: skiing in the winter, kayaking, golfing and hiking.

Dr. Andy Byrd will retire from CCR on July 26, 2024, but will remain as an NIH Scientist Emeritus.