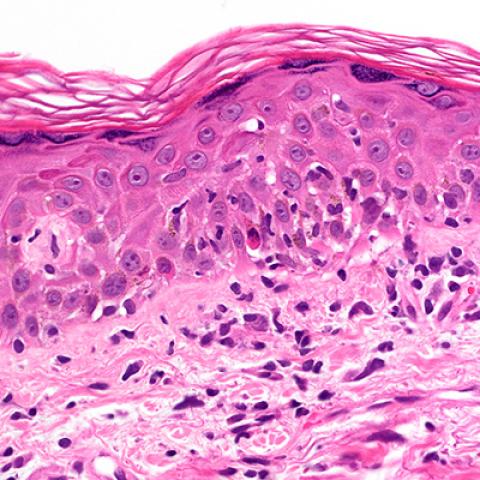

Photomicrograph showing graft-versus-host disease in the skin.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The drug cyclophosphamide is often administered to transplant patients to reduce their risk of developing a life-threatening condition called graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), but the underlying theory for why the drug is so effective may have been incorrect for years. The results of a new study in mice, published by Christopher G. Kanakry, M.D., Investigator and NIH Lasker Clinical Research Scholar in CCR’s Experimental Transplantation and Immunology Branch, and colleagues, appeared May 6, 2019, in the Journal of Clinical Investigation. The findings suggest that cyclophosphamide impairs the function of immune cells that cause GVHD rather than eliminating these cells completely, as was previously thought.

For many patients with advanced cancers of cells of the blood or bone marrow, the only curative treatment is a bone marrow transplant. But when any tissue is transplanted from a donor into a recipient, including with bone marrow transplant, there is a risk that immune cells within the transplanted tissue will launch an attack against the recipient’s own body, causing the potentially deadly condition called GVHD.

Since the 1960s, scientists have studied the effects of cyclophosphamide in the context of transplantation in the laboratory. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, under certain conditions in the lab during skin grafts in mice, the drug appeared to eliminate the immune cells in the transplanted tissue, called alloreactive cells, that attack the recipient’s tissue and cause GVHD. In the early 2000s, cyclophosphamide began to be used in patients to prevent GVHD and has been increasingly adopted in this clinical setting, and it has always been assumed to work by selectively eliminating alloreactive cells in patients.

Yet when Dr. Kanakry and his colleagues studied the effects of cyclophosphamide in mice after bone marrow transplantation, they had surprising results – the percentages of alloreactive T cells were about the same or even higher in mice that received cyclophosphamide than mice that did not receive the drug.

“What we found instead is that the alloreactive cells were becoming functionally impaired after cyclophosphamide. So even though they were persisting and could continue to proliferate and to infiltrate organs, they were not able to cause significant graft-versus-host disease,” explained Dr. Kanakry.

These results suggest that the drug impairs the function of alloreactive T cells just enough to stop them from causing severe GVHD but doesn’t eliminate them like the experimental skin grafts in the 1980s suggested. How exactly the alloreactive cells are impaired still remains unknown. Dr. Kanakry’s lab is conducting further studies to uncover these mechanisms.

“Beyond this direct effect on alloreactive T cells, we previously have shown the importance also of a cell type called regulatory T cells that controls immune responses,” he said. “In this study, we also have confirmed and extended our understanding of their role. We’re also now looking at the importance of other suppressive cell populations and ultimately trying to establish a new model of understanding. At this point, I’d say that we have knocked down the old paradigm and have created a framework for a new one. We’re now trying to fill in all of the gaps and really flesh that out in a more detailed and comprehensive way.”